tough business:

a parker site

“You Couldn’t Be Anything Else”: Gay Subtext in Richard Stark’s Parker

"My partner," he said.

"In the store?"

"Yes. Everywhere."

- A Jade in Aries (1970)

According to an autobiographical little tidbit on his website, the Stonewall uprising broke out while Donald Westlake was working on A Jade in Aries – the fourth novel featuring P.I. Mitch Tobin, and his investigation into the wrongful death of a gay man. It was an auspicious coincidence, but LGBT themes weren't uncommon in Westlake's work; he'd had his debut during the 'sleaze' novels craze of the 1950s, writing lesbian pulp fiction along would-be big names like Patricia Highsmith and Marijane Meaker. Still, Jade is often thought of as something of an outlier; being as it is a deep dive into the gay culture of the era with a sympathetic and layered portrayal of gay characters that's practically unheard of in the annals of mainstream crime fiction.

Donald Westlake was, of course, no stranger to crime fiction. At that very same time, he was still operating under the pen name of Richard Stark and writing the books he would be best remembered for: the Parker series. That was the true outlier in a career singularly concerned with LGBT themes – a gaycoded protagonist.

Gay characters are unexpectedly prevalent in the Parker novels. Initially referred to in passing with derogatory terms ("a latent fag with big hips" in The Hunter), eventually heavily alluded to (the young man with the bare midriff and "rouge on his cheeks" in The Man with The Getaway Face; Bob Negli and Arnie Feccio whose "life together was a series of compromises and adjustments" in The Seventh; Steuber in The Handle who was "Baron's whole world and equally so was Baron the world for Stueber"; Terry Atkins' mistaken impression of Billy Lebatard in The Rare Coin Score when he wonders if "Lebatard might after all be homosexual and had picked up – or been picked up – by an older man of the same type"; Ellen Fusco's ex-boyfriend in The Green Eagle Score who had "deep-seated hidden fears that he was a homosexual"), gay men ultimately become three-dimensional supporting characters towards the end of the original series (Paul Brock and Matt Rosenstein in The Sour Lemon Score, Leon Griffith and Jacques Renard in Plunder Squad).

Stark – or Westlake, if you prefer – was clearly following societal change but if the times were a-changing, so was Parker as a character. As the books went on, Stark's stance became clearer and clearer.

Parker has often been called a static character, as if he existed exclusively in the ‘rough, macho’ world perceived by a straight male audience unwilling to look beyond the first book; but what has often been ignored in any critical engagement with Stark's novels is the gradual thawing of Parker in the presence of his best friend and partner, flamboyant actor Alan Grofield. Parker's character development is subtle at first, then monumental. Butcher's Moon, the final book in the original series, follows the exact same plot as the initial trilogy (The Hunter - The Man with The Getaway Face - The Outfit) but Parker's motivation is no longer money, it's love. He has been transformed by his irrefutable fondness for Grofield.

In The Outfit, we're told "possessions tie a man down and friendships blind him. Parker owned nothing, the men he knew were just that, the men he knew, not his friends [...]". To that effect, Parker is cold, methodical, blunt, taciturn, repeatedly said to dislike small talk and most kinds of 'needless' social interaction. On the other hand, when he runs into Grofield in his introductory chapter in The Score, he greets him like an old friend.

The discrepancy is immediately apparent, and only grows throughout their appearances together. In that very same book, Parker comes across as betrayed when Grofield brings a girl along after the heist; he can only claim that he thought Grofield was a "pro" – as cutting a remark as Parker has ever managed, when professionalism is what he values most. While he and Grofield are discussing what's to be done with Mary Deegan, Grofield has "the look on his face that a man gets when he's done something too stupid to be possible and he knows it but still wants to justify it", as if he's suddenly understood the stakes he's playing with.

Later, Parker tries to drive Mary away by listing all of Grofield's faults ("[...] he's impulsive. He's smart, but he doesn't always act smart. Also, he doesn't pay his income tax. Also, he spends too loose and works too often.") and it's the most he's spoken at that point in the series. He displays an intimate knowledge of Grofield, a distinctly not romanticized view of his abilities, and he still thinks of him as a "good man", one Parker can rely on. These are not allowances Parker makes for any other character.

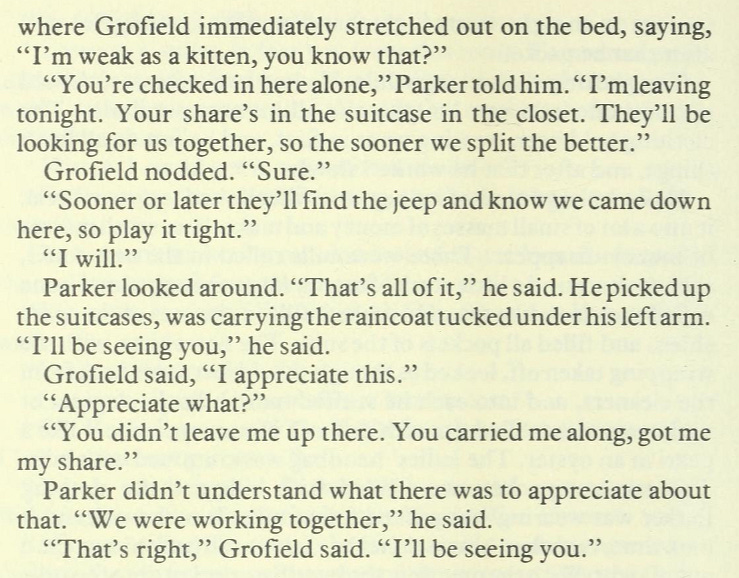

Two books later, in The Handle, Parker goes out of his way to save Grofield's life, and it's an act that marks the beginning of a pattern. Parker's willingness to come to Grofield's rescue is unique to their dynamic, their relationship completely singular in Parker's life. Where he's usually averse to touch, he lets Grofield sleep on his shoulder; Grofield calls him "love", "a true romantic", "a wonder".

The final chapter highlights the strangeness – the novelty – of a closeness Parker has shared with no other in a homoerotically-charged scene that begins with Grofield stretching out on his hotel room bed, and declaring that he's "weak as a kitten". Parker had gotten him a doctor after a close brush with death, a hotel room, and his share of the money. He justifies it all with a simple "we were working together", and it's an explanation Grofield accepts with an air of something knowing about him, deepened by the fact that Stark pointedly reminds the reader of Parker's seemingly uncharacteristic actions by having Grofield say he appreciates the gesture in the first place.

Parker's brief flings with women are portrayed as constant but unsatisfying, and take an unusual turn after The Handle. In The Rare Coin Score, sex is compared to a fight Parker gets into but it's only the latter he's said to prolong "for the pleasure of it", ranking a homosocial setting above heterosexual entanglements. It's the same book that positions Parker's attitude on sex with women as mildly dubious where his own consent is concerned, willing to use his body in the service of the job if it means keeping the heist going ("There were times when you had to push yourself a little to keep somebody else in the string content, and this was one of those times.").

In Stark's world, heterosexual sex is never equated with pleasure when it comes to Parker – it's functional, a much-needed release of adrenaline; which makes its disappearance in the latter half of the books all that more notable. Rare Coin also introduces Claire Carroll, Parker's would-be long-term companion, but their relationship is cold and dispassionate and each seems to serve a purpose for the other. Claire's role in Parker's life reads as a consequence of a piece of advice from Grofield in the previous book ("Without a woman on your arm, you'd look like forty kinds of trouble."), rather than the result of any genuine feelings.

The key to Parker's relationship with women lies in The Sour Lemon Score. A year before A Jade in Aries, that had been Westlake's first foray into a lengthy exploration of LGBT themes, and it still remains a striking one. Paul Brock and Matt Rosenstein – the gay couple at the center of this tale – are deeply compelling, deeply complex characters. Rosenstein is deep in the closet and drowning under internalized homophobia but he's also presented as a dark mirror of Parker, the man he could've been had he been any less self-aware. His repeated encounters with women, identical to Parker’s, are summarily presented thus: "Until four years ago when he’d met Paul Brock, his personal life had been bare but heterosexual. He'd taken sex the way he'd taken money, where he could get it and any way he could get his hands on it. It had never pleased him as much as money, but it had never occurred to him there might be any reason for that [...]. Brock was a faggot, and the relationship they had was sex-based, but that was just because living with a guy had business advantages and other advantages over living with a broad. Matt was still straight, and when he got a shot at a woman he still took it and it still wasn’t very good, but he was still straight."

Yet Rosenstein is undeniably and explicitly gay, simply acting out of self-hatred. When his boyfriend, Paul Brock, first meets Parker, he says that Parker reminds him of Rosenstein and that he "couldn't be anything else". The subtext nearly becomes text then, double-meanings brought to the surface. Brock's apartment becomes a significant part of Parker's story, he's fascinated by its "heavy veneer of masculinity" and two men living together doesn't faze him but rather puts him at ease. Deadly Edge presents Claire's house – symbol of the heterosexual domestic sphere – as a source of stress for Parker; when prompted to relax, he thinks, "there was no answer to that. He was on guard everywhere, it was natural to him." On the other hand, in a gay man's apartment, "Parker sat back in the chair and let his body relax while he waited."

If the dawning realization of his sexuality had nearly broken Rosenstein though, it appears to free Parker and allow him to develop as a person. For the remainder of the series, Parker is more aware of his emotions and no longer reacts negatively to what he considers 'irrational' feelings as he had in The Seventh. He hasn’t been softened but rather has grown at ease with himself, as if he'd taken to heart what he'd seen in Sour Lemon. His personal life is seemingly bare then as Rosenstein’s had been: Deadly Edge confirms Claire sees their arrangement as a practicality serving them both well, and in Plunder Squad Parker is actively repulsed by a woman making advances.

It all comes to a head in Butcher's Moon; the obvious intended finale for the original series of twenty novels but the grand finale to Parker's character arc, too. Returning to Tyler – the Midwestern town featured in Slayground and the beginning of The Blackbird – to recover the money they'd lost three years before, Parker and Grofield become entangled in local mob politics. Initially working together on a series of small-time hits, they've never been more in sync: Grofield refers to himself as Parker's "research girl"; a tableau of "two dark-toned zippered jackets laying on [the bed]" is presented in their seemingly shared hotel room as reminiscent of the men's clothing in two different sizes from Paul Brock's apartment in The Sour Lemon Score; when Grofield is on edge during a job, Parker reassures him by saying they're "all right"; and when they're forced to switch hotels, they relocate within the "pink-stucco walls" and "blue-slate roof" of the aptly named Princess Motel.

Undoubtedly aware of the innuendo, as his non-fiction work would later prove, Stark has Parker quite literally come out in the aforementioned Princess Motel. An would-be assailant in Grofield's room notes "the guy coming from the closet was already halfway across the room", and Parker once again saves Grofield's life without deviating from the pattern established in The Handle. His presence in the room isn't questioned, or the reader is otherwise meant to understand the single bed as belonging to them both. To drive the point home, Grofield proceeds to stand "naked and with a cake of soap in his hand" next to a kneeling Parker.

If the tone turns somber after this sequence, it's no less telling. When Grofield is shot and kidnapped, it's explicitly presented as the only way to hurt Parker. His subsequent quest for revenge puts the homoeroticism and subtext implicit to their relationship on full display. The importance of Grofield in Parker's life is near nonsensical in a platonic light, he's repeatedly told his safety is guaranteed if he leaves Tyler but Parker refuses to do so without Grofield. In fact, when he thinks Grofield is dead, Parker's first thought is to use the Outfit's headman to "break this town open."

The reality of his feelings is further emphasized by his distress at having received one of Grofield's severed fingers, which he keeps in a cufflinks box in his pocket for the rest of the book. When Handy McKay claims such sentiment is unlike Parker, that's Stark's pointed nod to the reader again. Parker agrees it's only Grofield he'd do this for and he launches into a speech ("I don't care if it's like me or not. [...] I'd like to burn this city to the ground, I'd like to empty it down to the basements [...]"), the intensity of which is said to startle his fellow heisters. A speech is practically antithetic to the man Parker is known to be, it's Grofield alone that has brought out passionate feelings in him.

It's an earlier scene that encompasses all that Grofield means to Parker though. In a mob boss' den, surrounded by enemies he's now practically pleading with for help, Parker says, "you're not leaving my partner there."

That's how Westlake comes back to a sentiment first expressed four years prior in A Jade In Aries. He proposes that Grofield is, indeed, Parker's partner everywhere. In fact, it's Westlake's nonfiction writing that not only encourages this reading but implies intent.

In discussing Raymond Chandler's work in a 1984 essay on genre featured in The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany, Westlake proposes that "homosexual content was one of the elements [...] that gave hardboiled stories their texture and fascination, and make them still alive today, more than forty years after they began." Looking at The Long Goodbye through that lens, he observes, "Marlowe's relationship with Terry Lennox, from the moment he picks Lennox up – literally and figuratively – in front of a restaurant called 'The Dancers' is inexplicable in any other way." Ultimately, Westlake asks, "if this is not a homosexual relationship, what on earth is it?" The question resonates in his own work.