tough business:

a parker site

“I collected Westlake as obsessively as I did Stark” - An Exclusive Interview with Max Allan Collins

Tough Business recently had the distinct pleasure of interviewing crime fiction author, screenwriter and comic book creator Max Allan Collins – best known for his long-running series characters such as Quarry, Nolan, and P.I. Nate Heller, although the comic aficionados among us may prefer Ms. Tree and Road to Perdition.

Max considered Donald Westlake a friend and mentor, and he kindly stopped by for a chat on their decades-long friendship, Nolan's origin story, and the infamous murder mystery weekends the Westlakes used to host.

1) How did you first discover Richard Stark's Parker?

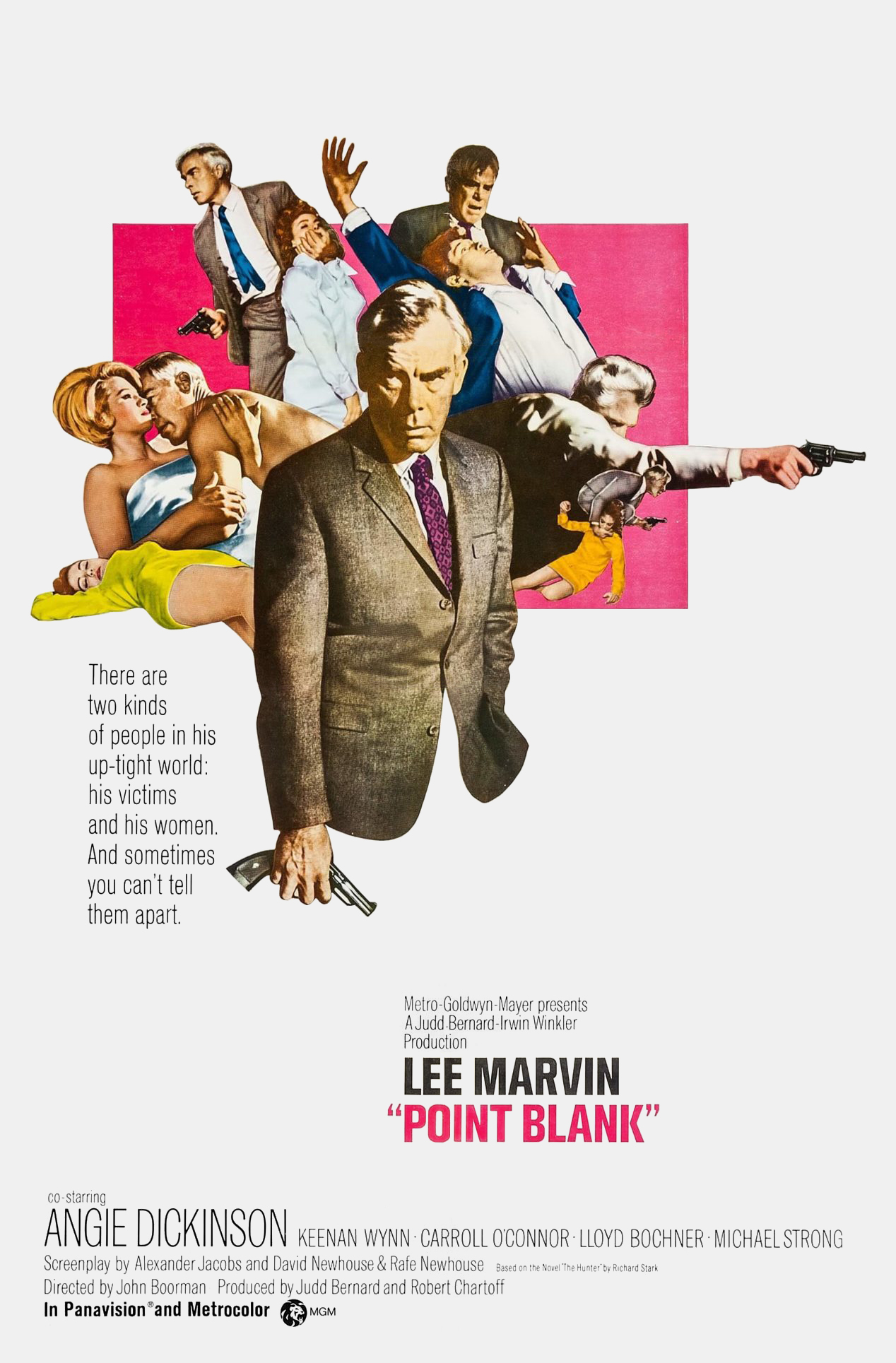

My then-girlfriend (and now, and always, wife) Barb and I saw Point Blank at a drive-in theater on the film’s first release. I remembered seeing a movie tie-in paperback on a spinner rack at a local supermarket, which stayed open all night… and I immediately went there, late that night, and bought it and the handful of other Parker reprints (and one new one) Gold Medal issued at the same time.

I eagerly consumed those books and sought the ones that Gold Medal hadn’t reprinted, finding all but one (The Mourner) at various used bookstores. When Barb and I honeymooned for a week in Chicago in 1968, we did (among the usual honeymoon activities) dine at terrific restaurants, go to plays, see movies, and scour sketchy used bookstores all over the city looking for The Mourner. And finding it.

Here’s an interesting, perhaps bizarre footnote: when I ran out of Richard Stark books, I decided I wanted to read something that wasn’t so dark, as a kind of palate cleanser. I picked up a paperback of The Fugitive Pigeon, a comic suspense novel by someone called Donald E. Westlake, and was hooked. I had no idea Westlake and Stark were the same writer. In my room at home (in my parents’ house), I had a shelf of honor for my two favorite writers – Stark and Westlake, separated by a slim metal bookshelf. I collected Westlake as obsessively as I did Stark.

In Anthony Boucher’s mystery-fiction column in The New York Times, I finally learned Stark and Westlake were the same writer (as well as Tucker Coe). I removed the metal book-end separating the two writers.

Don loved that story, by the way.

2) You've often spoken about the Nolan series being an homage to Parker. How did that come about? Did you start with the intention of writing a Parker-esque thief or did the character develop naturally?

I started writing novels in late junior high and on through high school, writing them during summer vacation and submitting them to publishers (unsuccessfully) during the school year. I did several imitation Mickey Spillane novels and one imitation Ian Fleming. In my high school years, I discovered Ennis Willie, an obscure writer of what were sold as softcore porn (but weren’t): Willie wrote crime novels about a one-named character, Sand, who had been a second-tier mob guy who betrayed his bosses in some fashion and was on the run. Sand also solved mysteries along the way, and – although the books were in third person – Willie wrote the best imitation Spillane I ever found (and I was looking).

As the years passed, I became one of a handful of professional writers who loved the Sand books and extolled them and Willie, who had written prolifically for perhaps three years and disappeared. All the latter-day discussion of Sand and his author, in fanzines and such (very much pre-Internet), chiefly by myself and the late Steve Mertz, finally caught Willie’s attention. He turned out neither to be Black (as we had speculated) or dead (which we had also speculated), but had gone into his family’s printing business for the rest of his working life. In retirement, he was thrilled to learn he’d been rediscovered and published two collections of the Sand novels (Sand’s War and Sand’s Game, still available at Amazon).

Sand and Parker are similar characters, to say the least, though there’s no sign either Don or Willie ever read each other. They first appeared at about the same time - they were just swimming in the same slipstream. But I made a connection between them, and that led to my one-name character, Nolan, developed while I was still at community college, in Mourn the Living. That novel wasn’t published till the later Nolans were, and can be found as a sort of “bonus feature” in Hard Case Crime’s Mad Money (with Spree).

3) Speaking of Nolan, the addition of his surrogate son Jon both differentiates him from Parker and humanizes him in a way readers may find easier to relate to. Did you find that relationship to be something that was lacking with Parker?

The first published Nolan novel, Bait Money, was fairly overtly – and the entire series is – born out of my enthusiasm for Parker (and to a lesser degree Sand). I had already started a long (again, pre-Net) correspondence with Don. He wrote me wonderful lengthy letters, and a lot of his mentoring happened in those.

He was instrumental - along with my University of Iowa Writers Workshop instructor, Richard Yates - in landing me my first agent, Knox Burger, famously the Gold Medal Books editor who revitalized John D. MacDonald’s career by getting him to create Travis McGee. Burger was a gruff, no-nonsense guy who was also Don’s agent – Don said of him, “Knox thinks tact is something you put on the teacher’s chair.”

I knew how heavily in debt to Don’s Parker my Nolan character was, and I had never intended Bait Money to be anything but a one-shot. In fact, Nolan died on the last page – he was designed to be, in a way, Parker at the age of fifty and old before his time, due to the harrowing life he led. So the book was meant to be a story about a tough guy’s last stand – the end of the Great American Hardboiled Anti-Hero.

Burger hated the ending, but I insisted on it, and he took the novel to half a dozen publishers, unsuccessfully. In those days, you had to submit a type-written manuscript on good bond paper – you couldn’t send a carbon, and anything with corrections (Liquid Paper included) was looked upon as amateur. Typewriter days for pro writers meant enduring a nightmare of making small revisions that required retyping pages, chapters and even books.

The sixth or seventh publisher spilled coffee on the manuscript. Burger said, “Since you have to retype it before I send it out again, change the ending. Let the guy live. Have the kid accomplice come back and save him.” I did just that and Bait Money sold next time out.

The publisher (Curtis Books) asked for a series – offered a five-book contract. I called Don and said, “Are you okay with this? Once is homage, twice is grand larceny.” He couldn’t have been more gracious. He said Nolan was a much more human character than Parker, made so by the presence of the younger character, Jon. There was a kind of father-and-son relationship (a recurring theme of mine). Also I had (as a college student in the late ‘60s) included things that hadn’t been in many, perhaps any, mystery novels yet – specifically hippies, the drug culture, and Beatles-era rock ‘n’ roll.

So, with Don’s blessing, I went ahead. It was my first series, and I thought I’d shut it down with the rather epic Spree, and am rather amazed I was talking into doing another not long ago for Hard Case Crime, Skim Deep. The same thing sort of happened with Don, who lost interest in Parker and shut him down with the expansive Butcher’s Moon, then returned almost twenty-five years later with Comeback.

4) You've referred to Mr. Westlake as a mentor. How did you first get in touch?

My first fan letter went out, effusive but fairly literate; he replied by return mail. Receiving that letter was one of the great events of my life. We had a long correspondence, lasting into the 1990's.

One afternoon I got a call from Don – we knew each other well by now, via letters, but I think this was the first time we spoke. I live in Muscatine, a little Iowa river town on the Mississippi. So the last thing I expected was to get a phone call from Donald E. Westlake saying he and his wife Abby were in Muscatine. I do not remember why, just that they were on their way somewhere and, without telling me, he had detoured to swing by. Did I want to get together?

Was he kidding?

My parents were out of town, so we put the Westlakes up there, and Barb and I ordered food from our favorite Italian restaurant and fed our new friends. It was a lovely, lovely evening. Don and I talked movies mostly, which had been what much of our correspondence was about.

That may have been when I learned Don didn’t always go to the movies made from his books. If he didn’t like the script, or other aspects of a production bothered him, he just stayed home. He did like Point Blank, however, though he thought the script was weak but the direction strong.

I can’t imagine a universe where I would not want to go to a movie made from one of my books.

5) One of our favorite anecdotes about Mr. Westlake comes from Charles Ardai, who told us he was exactly like he'd expected a writer of comic capers to be right up until he observed what he defined as a Richard Stark moment -- "it was like sitting down to a hand of cards opposite a professional poker player - you just know instantly how far out of your league you are." Did you ever experience anything like that?

No. I am ridiculously self-confident.

Don and I never had a falling out, but there was a point where I became enough of an established writer to not need, or desire, mentoring. He knew about my big project, the historical detective novel, True Detective. He told me 100,000 words for a private eye novel was not practical. He also advised making Nate Heller a reporter, not a P.I. (He was no fan of private eye novels). He read the book in manuscript and had problems with it. While I took some of his advice, but not much, that marked an end to a certain aspect of our relationship. Later he gave me a blurb for True Detective, claiming he did so because I had fixed it (again, I hadn’t followed many of his suggestions). True Detective was the Private Eye Writers of America “Best Novel” Shamus winner for 1984, and I have continued to write Heller throughout my career – there are 19 novels.

By the way, Don said Westlake became Stark when he woke up and it was raining.

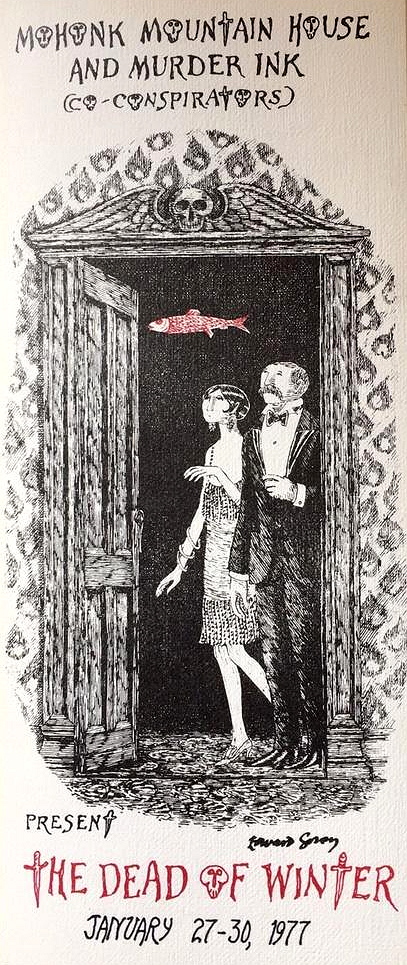

6) I recently read Transylvania Station, which is about the mystery weekends the Westlakes would host at Mohonk Mountain House, and you were mentioned as being one of the guests/speakers. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

I was privileged to be the murderer in one of those mystery weekend games. It was a wonderful experience. We met a number of well-known (Joe Gores) or on-the-rise (Harlan Coben) mystery writers; and the atmosphere, and food, were a summer-camp delight in the winter. Don put together a program of movies for the evenings, including the 1931 film of The Maltese Falcon, which I’d never seen before. He was a defender of that much dismissed first version.

I agreed with him (still do), though we both knew the John Huston version was the masterpiece. We discovered we’d both, at some point, followed the Bogart movie along in the book. It’s that faithful. And now I’ve written a sequel called Return of the Maltese Falcon, coming out from Hard Case Crime on January 6 (I’m allowed one plug, aren’t?). Don was definitely a Hammett man, not a Chandler acolyte, and he saw merit in Mickey Spillane, but was not a huge fan.

I wrote a mystery novel, Nice Weekend for a Murder (1986), about the Mohonk experience. I split Richard Stark and Donald E. Westlake into two characters, one of whom was the murderer (turnabout being fair play).

You mention Hard Case Crime, who have published many of my novels, in particular the Quarry series. Don had sent me a novel about a Bob Hope-type performer who was kidnapped. It was bylined Westlake but wasn’t humorous, which seemed to be the problem editors had with it. He hadn’t had any luck with it, and sent it to me, saying if I cared to, I could do a fresh pass and we’d co-byline it and “split anything” we hauled to shore. I was preparing to start the rewrite when Don called and said, “Stop! This new Scorsese movie, The King of Comedy, beat us to the punch – makes the book impossible to market.”

So I shoved the book in a drawer. But after Don’s passing, a few unpublished novel manuscripts emerged and Charles Ardai at Hard Case Crime was publishing them. I told him about the Bob Hope-type book and he wanted to see it. He published it as The Comedy Is Finished. A tiny bit of my writing is still in there – the final paragraph I believe, which I’d shown to Don and he approved of.

I am happy to have that novel out there, and complimented beyond words that Don turned to me. That we might have had a genuine collaboration is a huge missed opportunity.

Toward the unanticipated early end of his life, we had grown apart somewhat. The last time I saw him, and that we spent time together, was when the British Film Institute brought us in to showcase John Boorman’s Point Blank and Sam Mendes’ Road to Perdition. I have a vivid memory of a small moment that I perhaps overplay in my mind. In an upscale British restaurant, we were seated at a table for perhaps six or eight, our hosts and our wives and ourselves. From down the table, Don noticed me being questioned earnestly, being taken very seriously, by some fairly erudite “chaps” and I had a sense he was thinking, There’s that kid I knew who actually grew up to be a writer. My last moment with him was when, as we walked out, I fell in with him and told him how much his support and friendship meant to me. He was shy about receiving such compliments, but he smiled and thanked me.

My last contact with him was by e-mail, when I wrote him about the latest of his new batch of Parker novels and told him how terrific it was, and that it reminded me of how much impact he and his character Parker had on me and my work. He wrote me back warmly, really appreciating my words of praise, and expressing a human lack of confidence in whether he “still had his fast ball.” He sure did.

7) As both a crime fiction author and comic book writer whose work has been adapted for the screen, do you have a favorite Parker adaptation? Have you read Darwyn Cooke's graphic novel adaptations?

Point Blank remains the best film from Don’s work. He would write such great premises that Hollywood would be attracted to the set-ups, then ignore the rest of the great book. Bank Shot, anyone?

Before I touch upon the graphic novel adaptations by Cooke, I should discuss a few comics-related things about Don and me. When we corresponded, and he learned I was a comics fan (not yet a writer of comics), we sent things back and forth. I showed him Richard Corben’s Den, for example, and various underground comix, and he loaned me Harvey Kurtzman’s rare, ill-fated Trump (Hugh Hefner’s attempt to do a comics-oriented slick magazine – ran two issues). So Don was hip to comics. He gave me a blurb for my graphic novel Road to Perdition, which he seemed to like. When the movie came out, and got lots of press and praise, he called to congratulate me on “riding the Zeitgeist.”

Calls from him were rare but a treat. Once when a New York Times review of a Heller short story collection included an introduction making it sound like I had passed away, Don called, and when I answered, he said, “Good! You’re alive.” And hung up.

When I landed the job as the writer of the Dick Tracy comic strip – my first big break - Don and his wife Abby invited Barb and me to stay on a whole floor of their apartment while we were in NYC for an event related to my being signed by the Chicago Tribune Syndicate. They threw a cocktail party for us and invited publishing friends to meet and congratulate me. Among the attendees were Otto Penzler, Martin Cruz Smith, and Lawrence Block. Obviously this was an incredibly gracious kindness.

After I became an established comics writer, we talked seriously about me doing Parker graphic novels, but the publisher wanted originals and Don would only allow adaptations. So that fell through.

Now here comes the awkward part.

I don’t like Darwyn Cooke's Parker adaptations. Cooke was a terrific artist, but his cartoony take on Parker strikes me as wrong. Something more “real,” frankly like Road to Perdition’s artist Richard Piers Rayner might have provided, would have been more appropriate. Or something grittier like Joe Kubert.

Don’t get me wrong. Both Westlake and Cooke were geniuses, gone much too soon. I just – personally – don’t think they made a good fit. But anyone who enjoys them, great.

8) In a January 2009 tribute to Mr. Westlake for The Rap Sheet, you wrote that there are several references to your work in Parker and Dortmunder. Are there any in particular that stand out?

I don’t recall any, just that Don would do that now and then. I think Butcher’s Moon might have included me in a dedication to several of his friends. And I know, a couple of times, when he needed to name somebody who was just an off-stage spear carrier or something, he’d use my name in part or in whole.

That’s a disappointing answer, so I’ll end with something better.

When we did the Mohonk mystery weekend, Don had me do a presentation about Dick Tracy, which was my calling card at the time. He introduced me, cheekily, as having written a series of novels (Nolan, obviously) that made me the Jayne Mansfield to his Marilyn Monroe. When I got to the microphone, I said, “I consider myself more Don’s Mamie Van Doren.”

He loved that.

I am pleased, even thrilled, when a Richard Stark fan likes the Nolan novels. I told Don once that the Nolans were the methadone to his heroin. But there’s only one Parker.

A version of this also appears on Max Allan Collins' website, which includes some great pictures of Max with Mr. Westlake.