tough business:

a parker site

Some Notes on Donald Westlake's Use of Stereotypes | Jean-Patrick Manchette

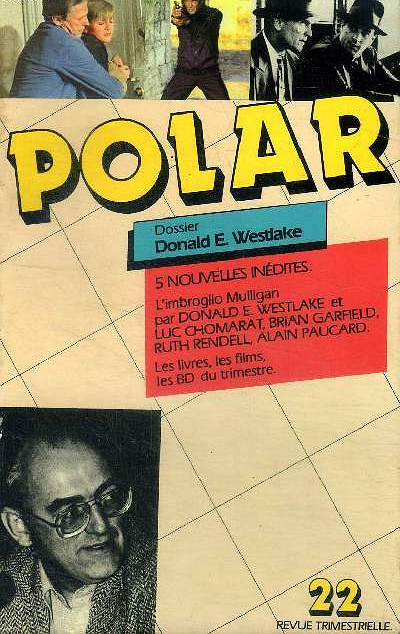

The January 1982 issue of French crime fiction magazine Polar #22 featured an analysis of Donald Westlake's various pseudonyms by renowned novelist Jean-Patrick Manchette. We've got the honor of presenting the piece in full below, translated by Doug Headline.

Some Notes on Donald Westlake's Use of Stereotypes

1. Parker's saga is also an extreme demonstration of stereotype engineering. Stark/Westlake certainly varied his plots and made his lead character evolve; but as soon as the Parker novels did become industrial literary products to be turned out on a regular basis, almost all of the novels began to follow the same assembly-line steps: preparation of the heist; adequate execution; complications due to the inept or malevolent nature of a non-professional member of the string; bloody outcome. Each of these four steps could in turn be subdivided into mass-produced individual parts. For instance, in the “setting up the heist” section, the same mandatory set-pieces are used in whole or in part every time: the first plan is no good, Parker imposes another one to the crew and imposes himself as team leader, without enthusiasm, but because he needs the money; the crew itself is like a batch of spare parts (one or two behavioral traits will define the shape of each of these parts); the financing and, above all, the instrumentation of the hit (weapons, vehicles) call for a few “objectal” sequences (see, for example, the ten pages in The Man with the Getaway Face devoted to the purchase and relocation of an old truck that has an oil circuit in poor condition).

2. In the writer's mature period, the “Westlake” signature is mainly reserved for humorous works. It's no coincidence that some of Westlake's work is a pastiche of Stark's novels. The pastiche is essentially a stereotype, a commentary on the stereotype, a sarcastic remark on the stereotype. The extremity of sarcasm is reached when Westlake's heroes try to implement the brilliant plan of action that worked so well in a Stark novel, and now works so poorly.

But alongside such explicit parody, the self-mockery was already visible in the grotesque reworking of the assembly-line structures (preparation, instrumentation, execution, complication, etc.), or when the well-planned, professional Parkerian coup, devolves into end-of-banquet enormities: a thief swallowing his loot, a gang robbing an entire bank (the building itself).

If the recent Castle in the Air at times made me yawn (and do forgive me for that!), it's because it once again piles up all the stereotypes of self-deprecating pastiche (stereotypes with which we were already familiar), just as the “serious” Butcher's Moon, by bringing together all the characters and all the elements of the Parker saga, signalled the wear and tear of this very saga, and was no longer worthwhile for what it repeated, but for what it revealed and what was new in it (the “insensitive” Parker's tenderness towards Grofield).

Just as some authors have ironically echoed Stark's stereotypes (see, in recent times, some of the statements made by Lawrence Block's elegant burglar hero, Bernie Rhodenbarr, in The Burglar who liked to quote Kipling), so too does Westlake the humorist not only attack the stereotypes that his alter ego Stark uses, but those others make use of.

Castle in the Air is just as much a parody of the international super-thriller. The 1977 A Travesty is a firework display of British-style “detection”, in which the hero solves just about one “case” per chapter, before falling victim to an infinitely crude, inelegant and unfair police frame-up. “Framed for a murder I had committed!” exclaims the narrator, disgusted.

In a similar way, Two Much is clearly an exercise in theatrical farce. Without calling upon French authors, we can think here of the American Broaway comedies (those guys do have authors of Neil Simon's caliber), and we'll immediately witness what we had already guessed: a guy who pretends to be twins himself in order to sleep with twin sisters not only isn't a bad person in absolute, he's also good subject matter for a novel. In the ensuing combinatorial festivities, I see only one possibility that was overlooked by the writer: since one of the two sisters sleeps with the hero, mistaking him for her sister's lover, it would have been pleasing, in this moment, if his bed partner had been not, of the two twins, the one he believes he is sleeping with, but the other posing as her own sister. (I'm afraid my suggestion is obscurely worded, but that's all Westlake's fault).

3. Let's not get into Adios Scheherazade, a cult book for fetishists; its very subject is the stereotype, dealt with in such a way that it obviously speaks for itself. Let's also leave aside Westlake's “first career”, that of The Mercenaries or Killing Time. In that period, the author worked within the stereotype, not on it. He worked efficiently with conventional subjects. He dabbled in all genres, and would continue to do so.

At the end of the Sixties, for example, in the midst of his Parker boom, he still came out with Up your Banners, a socio-humorous-racial “relevant subject matter” novel that is also an essentially moralistic book. (And I can just imagine Westlake smiling at his keyboard, smirking, and muttering that he's going to make his own Blackboard Jungle, in a jiffy! But I could be wrong). In any case, the greatness of the writer is only fully apparent if he deliberately and openly works on the stereotype. Thus, the principle of the division of labor also leads him to divide his works between several trademarks: his several pen names. From now on the consumer will know that we get thrilled with Stark, ruminate bitterly with Tucker Coe, and most of the time laugh with Westlake — although this last and first signature is the one that holds for the readers, and holds for itself as well, the most surprises.

4. When Donald E. Westlake becomes a master of the noir novel, and probably the most masterful of all masters of his time, the whole hard-boiled school has come and gone. To sacrifice to the genre, you don't have to be a sad-faced knight in shining armor; but you do have to wear a tin dinner plate as a helmet. Westlake's humorous disillusionment, moreover, concerns a genre that was already the great genre of modern disillusionment. When Don Quixote has already passed by, gimlet in hand, what can one do? Include in your work everything that makes Don Quixote a trinket out of Walmart's. Include, through imitation and derision, everything that makes the Noir novel a “cultural” object. Without ever forgetting to show that you are a part of this object's history. The use of stereotypes, when openly presented as such, becomes a tribute to the greatness of a genre. By joking around, the author makes it clear that he's not dressing himself up in the spoils of the genre he is honoring. Westlake is a featherless Indian chief, a maestro in his underpants, and proud of it, his magic wand his only weapon.

5. The stereotype has become totalization. When the Noir novel is dead, Westlake makes no secret of the fact that he keeps its heart beating in vitro. Hence his meticulous enumeration of trademarks other than himself, names of weapons, names of vehicles, and so on. The craftsman works on the catalog, where he has saved for himself at least three entries (Westlake, Stark, Coe). Compare this tongue-in-cheek homage with the messy blasting-up attempts that followed immediately afterwards (“the neo-Noir”). Those who lacked height wanted to rise above their genre. Westlake's greatness lies in always working against his own elevation.