tough business:

a parker site

A Crown for Don | Jean-Patrick Manchette

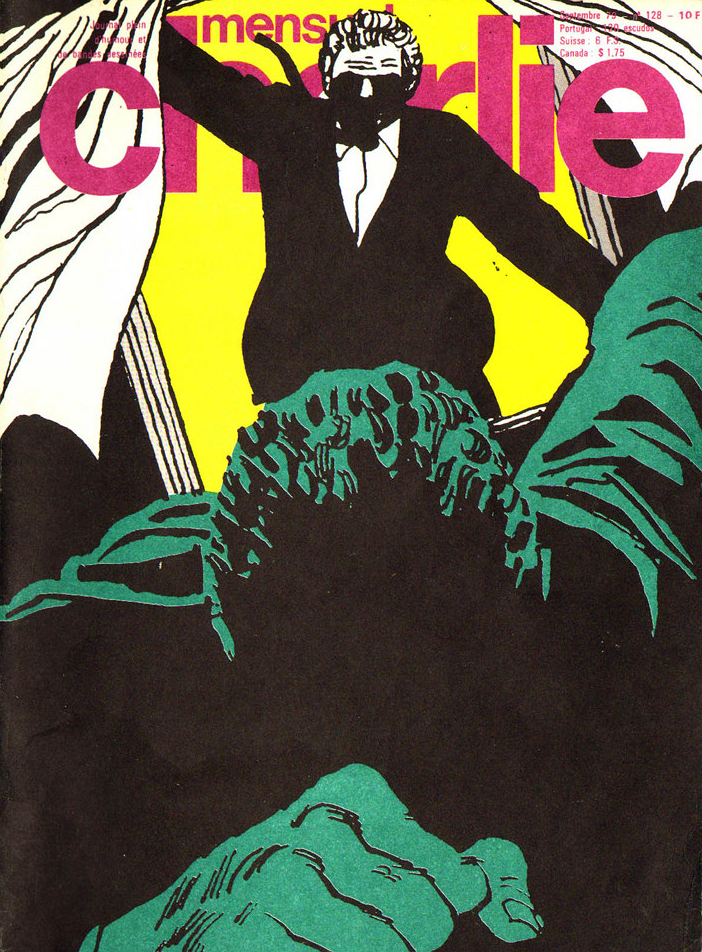

The September 1979 issue of the monthly French comic book magazine Charlie Mensuel #128 featured a fascinating piece on Donald Westlake by renowned crime novelist Jean-Patrick Manchette. We've got the honor of presenting the excerpts pertaining to Richard Stark and the Parker series below, translated by Doug Headline.

A Crown for Don

The key to Donald Westlake, the key to the semantic range, is precisely his all-round skill, and thus Westlake-Stark-Coe's personal relationship to his own skill. Westlake's works belong to the period of decadence of the classic detective novel. These works were created and presented at a time when the detective novel had ceased to be the great moral literature of its time, and when, at the same time, the detective novel form had, for some time already, been reclaimed and trivialized by merchants of mere imitations (Hadley Chase, Cheyney, Spillane). These merchants of imitations are not necessarily without quality or talent. But Westlake has more talent than they do, and he's smarter than they are. He envisions and practices the Noir form as well as they do, and he possesses the knowledge that goes with it.

[Soon after he began writing crime fiction,] Westlake abandoned the pure stylistic exercise aspect of it — but at the same time, he did not really abandon it. Westlake's best-known and best-selling production was to be the Richard Stark series, an ironic exercise in style. […]

The reason for this is, first of all, that in the Stark series, Westlake gives the crime fiction form a particularly modern, attractive and marketable spin. Stark's hero is a robber named Parker. Parker is self-employed. (Like Walter Matthau in Don Siegel's enjoyable little Starkian film Charley Varrick, he could almost wear a jumpsuit with the words “Last of the Independents” on the back.)

In most of his adventures, Parker forms a team for a heist, the heist is brilliantly executed, then a complication arises through the fault of a secondary character who doesn't have Parker's qualities, and extremely violent events ensue, before Parker heads off on a new adventure, a new job.

He often ends up with money. That's how he earns his living, thanks to the best of his qualities. What are the best of his qualities? Insensitivity, brutality, stubbornness, professional ability, strength. Parker is a savage. The subtle Westlake (Stark) did not fail to nuance his hero's mindset, as he made him not entirely insensitive, and so on. But the skilled Stark (Westlake) did even more to outline in bold strokes this character's persona: Parker has sinews like ropes, he coldly kills anyone who bothers him, he's half illiterate, he's an animal when it comes to making love (but abstinent when he's on a bender), etc. Parker stands on his own. Parker is self-sufficient. He's a wolf.

Of course, we immediately recognize in Parker an old American dream, now much degraded. The handsome cowboys may have fled away from the barbed wire, the aggressive women of the East, and down South to the Río Bravo, and (even farther out), modern civilization, i.e. wage-labor, has caught up with them everywhere. To keep their independence, unless they become private detectives, they have to become robbers, and less and less ethical and romantic robbers at that. […] In several early Stark novels, and particularly so in The Outfit, Parker confronts the Mob, and is explicitly shown and told that, if he momentarily triumphs, it's only because the Mob has been softened by wage labor.

Parker is a compensatory fantasy for salarymen. With him, Stark-Westlake has hit the bullseye, commercially speaking. Merchant of illusion, merchant of imitation. But that's not all of it. For, unlike self-satisfied merchants, Westlake-Stark-Coe never ceases to warn the reader (the customer) about the exact nature of the merchandise he is producing.

His warnings come in two different ways, which are perhaps one and the same: with humor and emphasis; with excess and irony. The avowed irony of his overtly humorous books. But there's also irony in the outrageously gloomy [Tucker] Coe books, and irony in the Stark books, where Parker-the-savage, chasing his loot with insane determination, must have left over fifty corpses behind him in less than twenty novels. That irony culminates in Westlake's own pastiche: his heroes Kelp and Dortmunder go so far as to use a Richard Stark book as inspiration for a job (and, of course, everything that worked like clockwork for Parker goes wrong for Kelp and Dortmunder...).

A fitting irony. When the era of the great classic crime fiction has passed, and yet you love crime fiction and want to write exactly that, the Westlake solution is undoubtedly the most elegant of all.

- Jean-Patrick Manchette, May 1979