tough business:

a parker site

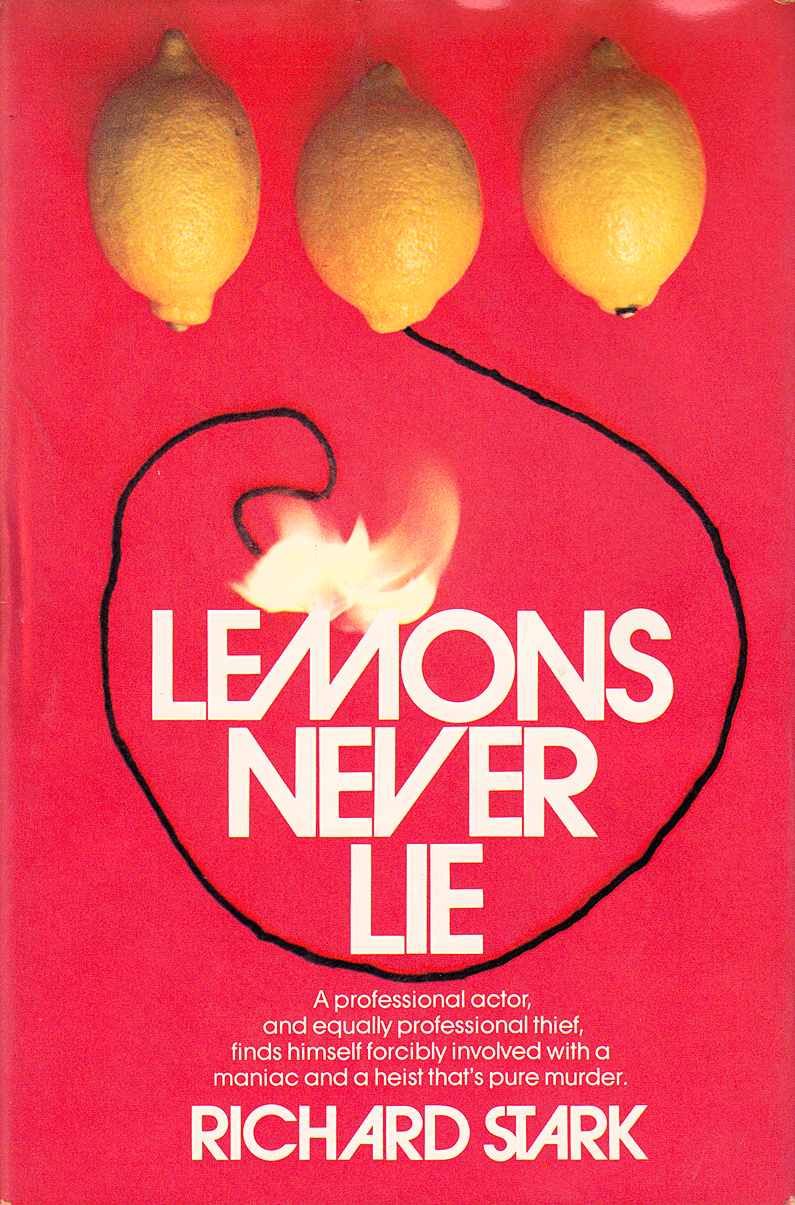

Lemons Never Lie

Published: 1971.

AKA: The Man Who Fought Las Vegas’ Mad-Dog Heisters.

Cover Artist: Milton Charles.

Publisher: World Publishing Company.

Cover blurb: "A professional actor, and equally professional thief, finds himself forcibly involved with a maniac and a heist that's pure murder."

Synopsis: Grofield's luck couldn't be worse but when he walks out on a job and the man in charge tracks him down, he finds out there's still further to fall.

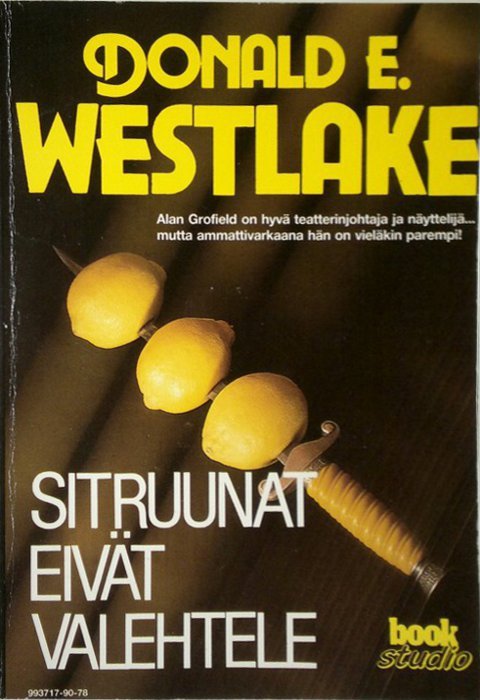

Gallery:

Review:

Lemons Never Lie, the fourth and final novel starring a solo Alan Grofield, makes for an especially interesting entry in Richard Stark’s canon. Widely received by readers as a return to form, Stark’s story is in actuality a departure from Parker’s world as sharp and disorienting as any previous Grofield adventure had been – if not more so. If the previous trio of solos had been more obvious in their intentions, having given us exotic locations and international intrigue, then Lemons certainly treads familiar ground but ‘familiar’ is all it is. The reader gets the impression of having stepped through the looking glass. As is customary for Stark, it’s a rich and layered narrative, its texture given primarily by an exploration of Grofield’s identity.

To begin with, one of the novel’s most striking moments comes in the fourth chapter of the second part (“Mead Grove, Indiana”) in the form of the sheer artificiality of Grofield’s personal life. In Stark’s work, the domestic sphere is always a psychological entry point into the inner workings of the character to whom the home belongs; Deadly Edge tellingly has Parker equate Claire’s ‘sense of home’ to his sense of identity. To that extent, Grofield lives on stage – quite literally. The description of Grofield moving from the ‘bedroom set’ to the ‘living room’ set to the ‘dining room set’ is novel at first, and chilling on a second glance. These are literal set pieces on the stage of his barn theater, and when Grofield sits down for dinner, he’s got his ‘place’ and his lines and his cues. He’s playing at a blissful domestic life with his wife, Mary Deegan, who works in a supermarket to support the two of them.

It’s pure artifice, Grofield the devoted husband is as real as Grofield the spy from his later fantasy during the heist in St. Louis. With that moment specifically acknowledged as a coping mechanism (“bringing back the old habit for the sake of calming his nerves and staying in character”), one has to wonder what exactly Mr. Stark intended to imply about the state of Grofield and Mary’s marriage.

Grofield is completely under the impression that he can keep his life at the theater separate from his work, but it couldn’t be farther from the truth. His tendency to let his theatrical talents influence him while on the job in his other appearances comes to a head in Lemons Never Lie. Grofield doesn’t pay his taxes and expects no consequences, his work doesn’t tangibly affect his life in Mead Grove because real, dangerous things don’t happen in theater. Unfortunately, Mary suffers the most when these two spheres of Grofield’s life intersect.

After all, Grofield’s week after leaving Mary is more vacation than revenge quest, seeing as he’s only interested in tracking down his money and riding horses and not calling his wife, thinking bitterly that “he had nothing to say to her yet.” He offers little comfort to Mary after she experiences the most traumatic event of her life, so unbearable that she can’t put it into words. To Grofield, it doesn’t seem to have a place in their perfectly staged life. He's almost unaffected by it as he thinks of sex with Mary as “cumbersome and difficult” afterwards, and has to be begged to stay overnight with her. Meanwhile, Mary had lived with Dan Leach’s corpse for days, or as Grofield refers to it, the “thing” under the white sheet on their sofa. Grofield’s total detachment from the violent acts around him is one of the novel’s major themes; he tells Dan not to hurt Myers in front of him, he deliberately avoids looking at the bloodied corpse of Dan’s wife, and he reacts with blatant disgust when he has to dig through Myers’ blood-soaked pockets for his money.

Grofield's actions throughout the novel are very nearly antithetic to the average Parker job. Where Parker is efficient, single-minded, detached and driven, Grofield appears to have only a vague understanding of the requirements in his line of work. He uses an alias to check into a hotel, but freely gives his accomplices his real name; he commits arson to hide his prints when a simple clean-up job would've attracted far less attention, his preferred method of torture appears to be mild discomfort. Again echoing Deadly Edge, Parker's thoughts on amateurs seem downright personified in Lemons Never Lie – Grofield knows how to do some things right, but not the reason for doing them.

Ultimately, Grofield's final solo novel is built firmly on the foundation of The Damsel, Dame and Blackbird. Lemons does not, and cannot, exist in the singular; its genre may be the closest to Parker's so-called violent world but the narrative elaborates on themes and characterisation introduced in previous adventures: it completes a complex, three-dimensional portrait of Alan Grofield.