tough business:

a parker site

Parker 1969 - La Proie: An Efficient Take on Richard Stark’s Most Complex Novel

The long-awaited French-language adaptation of The Sour Lemon Score has finally hit the stands and after our chat with the creative team earlier this month, we couldn’t be more excited to dive into the pages of the first Dupuis graphic novel released under the Aire Noire imprint. La Proie is as blunt, purposeful, direct and efficient as its protagonist – sometimes losing the finer touches of Stark’s original novel but never its edge.

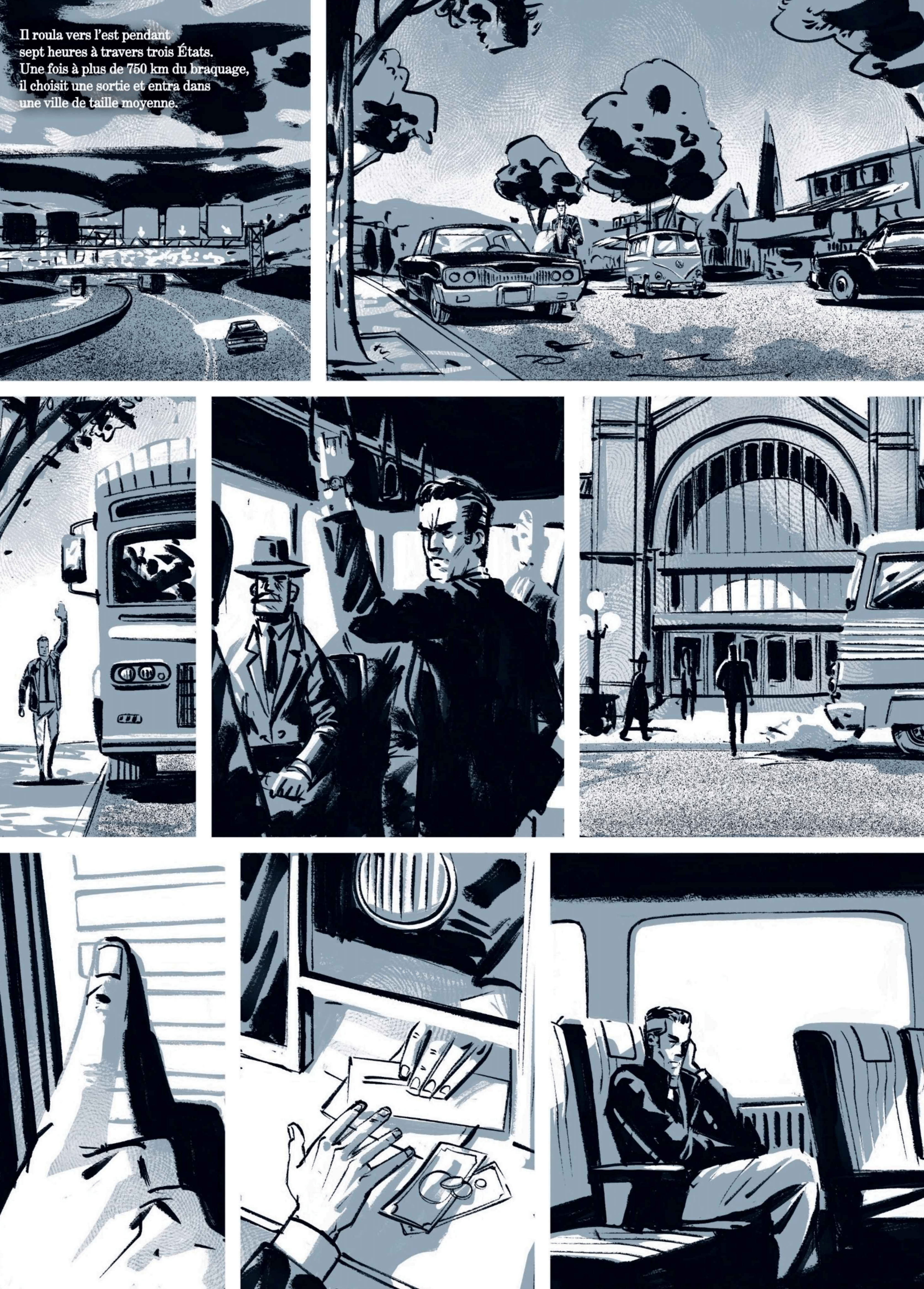

Visually inspired by Darwyn Cooke’s hit graphic novel adaptations published by IDW, the book stands well on its own with writer/translator Doug Headline and artist Kieran at the helm. Once Cooke had established the visual language of what many would still consider the quintessential portrayal of Parker’s violent world, the real task of any follow-up is that of constructing its own identity. To that end, La Proie succeeds where others might have failed. Kieran’s use of texture – the fingerprints smudged all over in Parker’s wake – is innovative and downright thrilling, his stylized line art an homage to Cooke but never an imitation.

The graphic novel is split into four parts, the same as The Sour Lemon Score itself and indeed the average Parker book, each with its own strengths. The first part follows the novel closely, with dialogue kept nearly identical to the original text and a near-cinematic ‘show-don’t-tell’ approach marking Parker’s journey after George Uhl’s double-cross. Narration is sparse throughout, with the adaptation often hinging on the strength of Kieran’s storytelling.

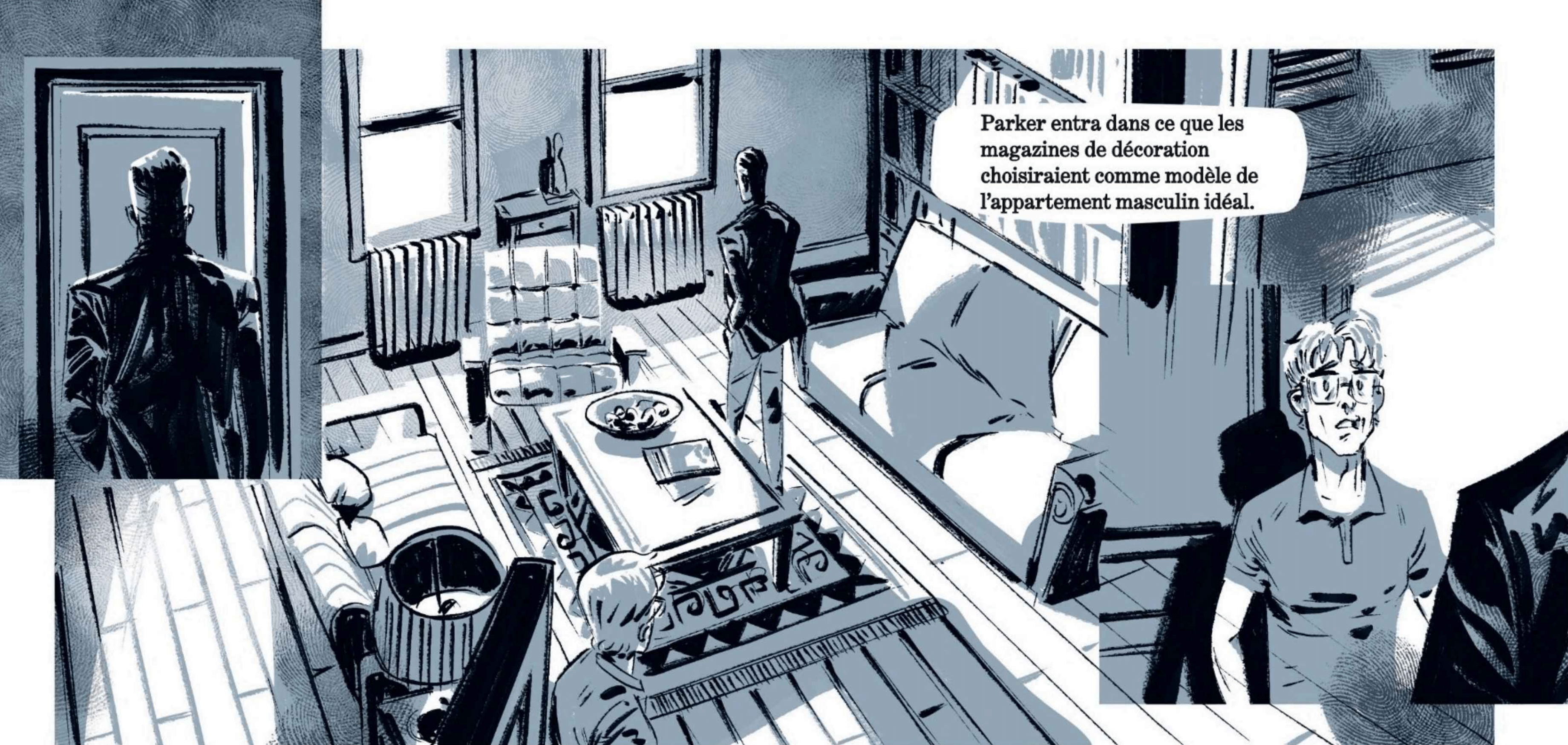

La Proie seems to somewhat lose momentum during its second act though. Time spent with side characters leaves us without enough attention paid to the nuances of Parker's first meeting with Paul Brock, whose personality doesn't show in the graphic novel as well as it does in the original book. The power dynamics that come into play with Parker here, and are later further explored during Matt Rosenstein's point-of-view chapter in Part Three, are first displayed during these interactions. Brock's teasing and utter lack of fear are absent, and instead are replaced by a blatantly nervous look.

However, Brock and Rosenstein's interrogation of a drugged Parker is inventive, and Kieran's artwork expertly captures the confusion and fear. Escher-like impossible triangles frame Parker’s descent into the watery depths of his own mind, powerless to resist the drugs he’d later use on Uhl, in an impressive and well-composed two-page spread.

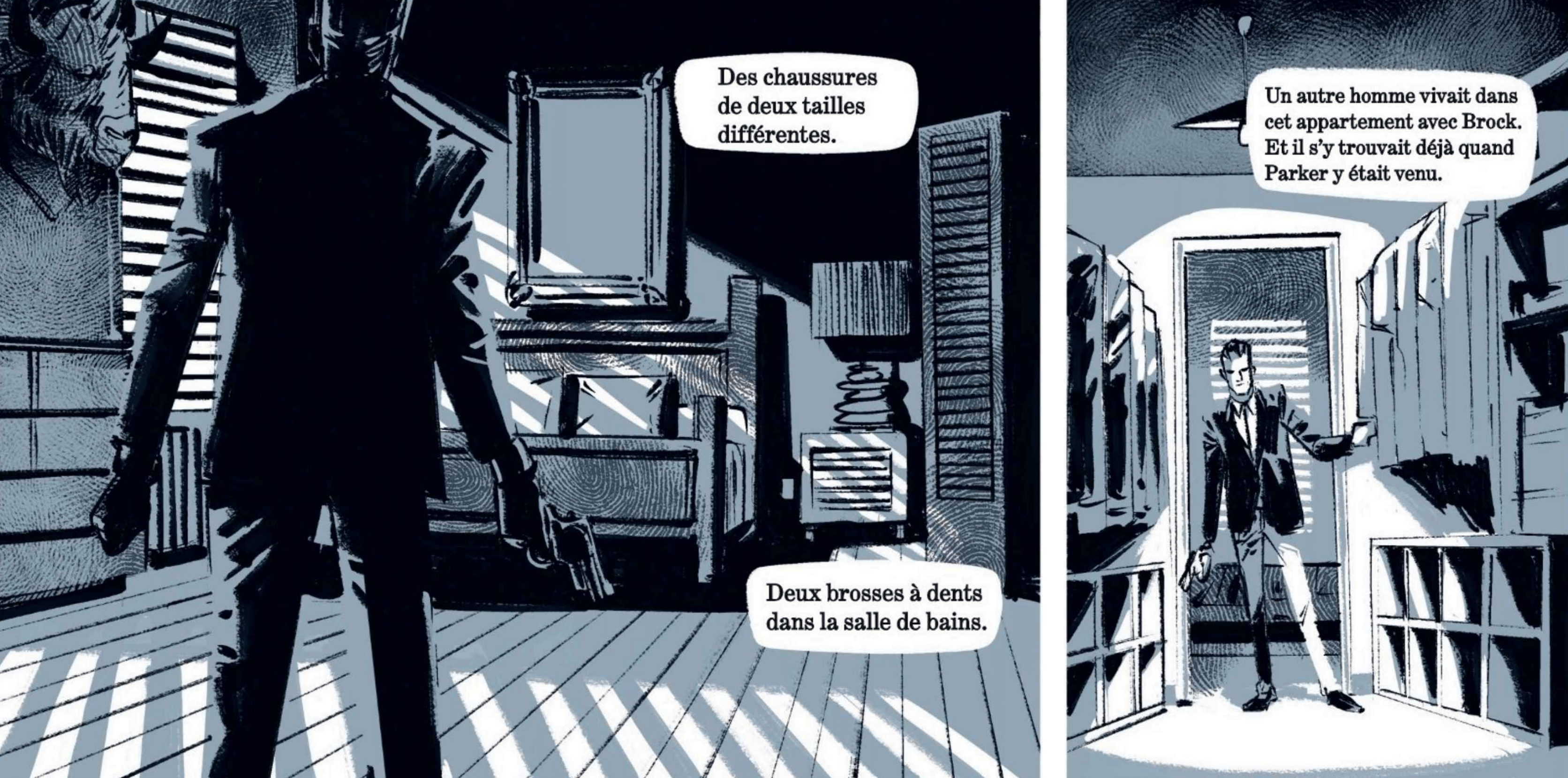

If Paul Brock's introduction is significantly shortened, so is Parker's return to his apartment. Stark's worldbuilding becomes subtextual – the signs that Brock is living with another man are stated but not made obvious visually. A reference is made to two toothbrushes on the sink and the clothing in two different sizes, but we only see a brief shot of the bathroom and in the walk-in closet, the clothes are segregated entirely. The Sour Lemon Score's palpable feeling of intimacy between the two men lacks depth here, narratively and visually.

Despite its streamlined approach, the scene is not without merit. On the bedroom splash page, inset panels like diagrams point to everything Parker’s found in the room; an efficient storytelling device that uses the medium to its advantage.

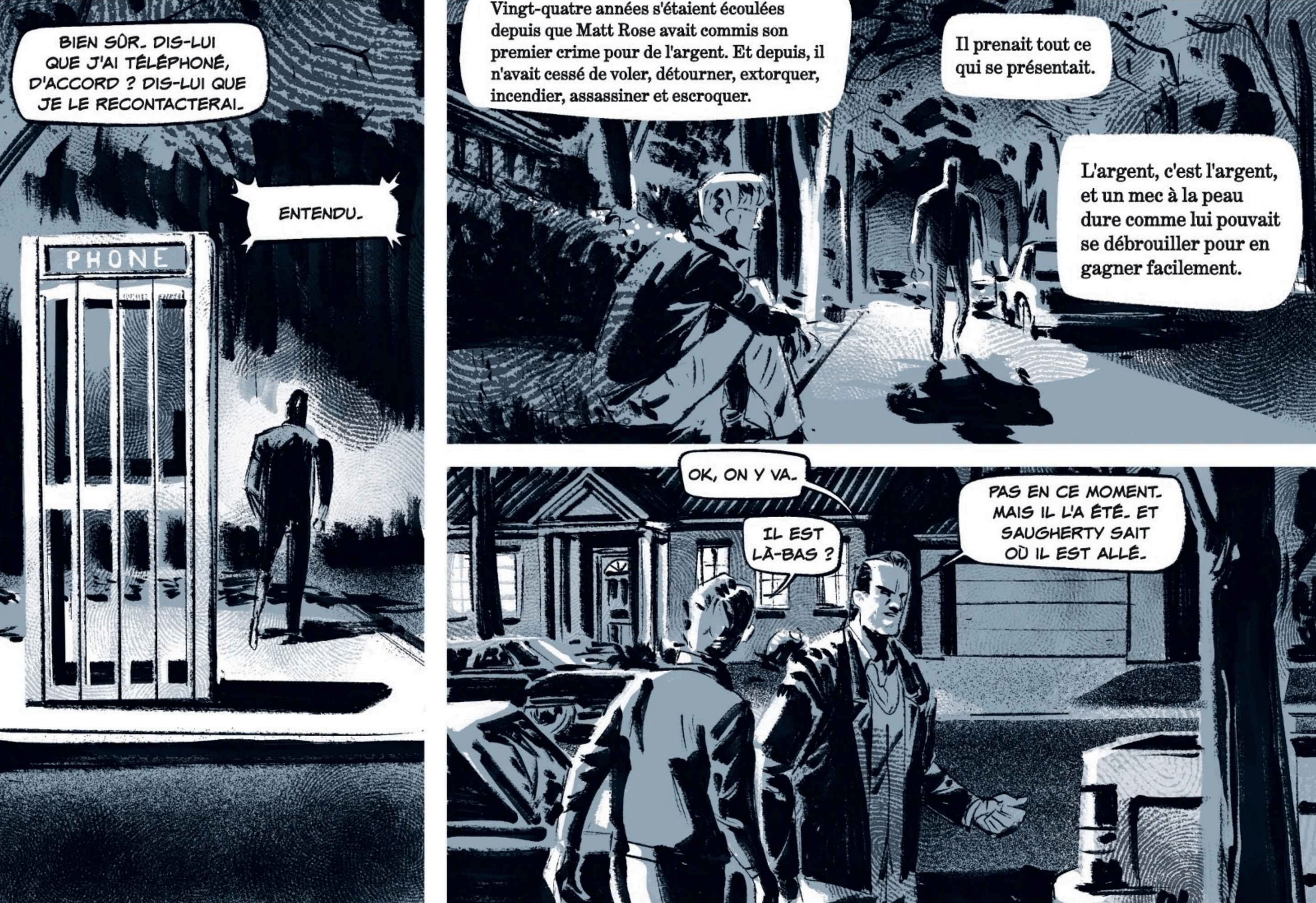

Though readers are treated to an impressive array of memorable character designs, the third part of the graphic novel tends to lack focus. In the absence of chapters, we circle through the supporting cast's various points-of-view without much to differentiate between them; most are truncated, Matt Rosenstein's origin most of all. Although clearly well-intentioned, the contemporary La Proie does not allow itself to portray the exploration of internalized homophobia Stark had written about with such frankness in the 1960s at all.

Rosenstein’s sexuality isn’t just the most complex part of the original novel, it is also the key to understanding the primary antagonists. His actions are not excused but explained, and La Proie’s concealment of Rosenstein’s identity early on doesn’t pay off when he comes across as a one-dimensional character in lieu of the radical themes Richard Stark had undertaken. It’s a sacrifice made in the service of a more efficient adaptation, but it does rob the story of some of its fascination.

The final page deviates from the novel even further, leaning into common perception of Parker as a James Bond-esque smooth operator when The Sour Lemon Score had signalled the beginning of the losing streak that’d follow him around until the end of the first series – a far cry from the carefree days he’d known off work in the early novels.

If La Proie doesn’t quite stick the landing, it is no less of an enjoyable read. A tight, no-nonsense adaptation that would delight any crime fiction enthusiast, it makes for an exciting return to Richard Stark’s timeless, genre-defining classics. For the new recruits to the business, it’s as effective of an introduction to Parker as any other.