tough business:

a parker site

The Italian Hack Job: Richard Stark's Parker & Foreign Language Editions

(This article contains explicit discussion of homophobic language. Reader discretion advised.)

The back of the first edition of Butcher’s Moon, the twentieth and final book in the original series of novels written by Donald Westlake under the pseudonym of Richard Stark, boasts the following: “Beginning with The Hunter in 1962, the Parker series has established its own niche in the thriller genre, and has been translated into nine languages around the world, including Norwegian and Japanese.”

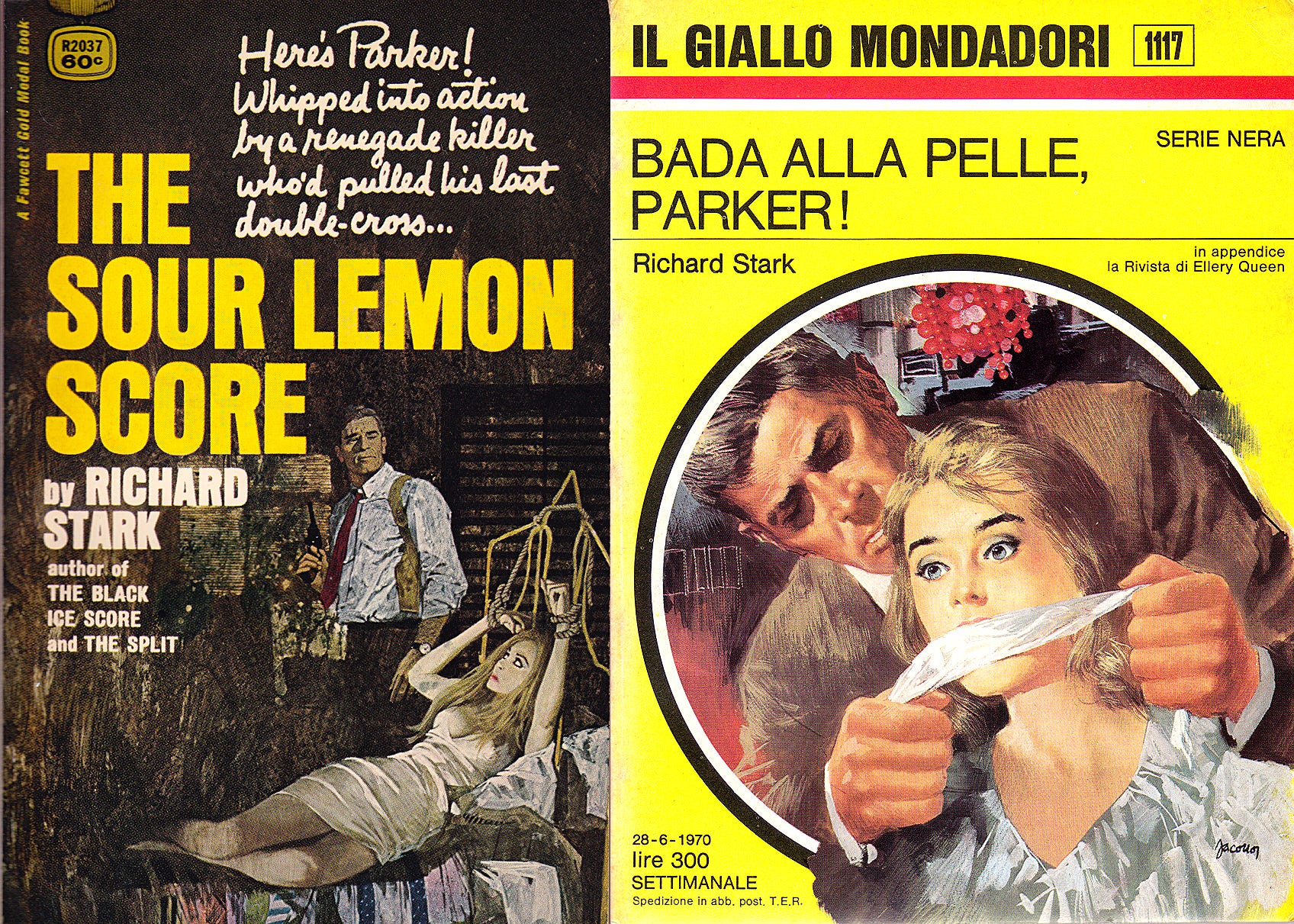

It’s a well-deserved claim, Parker has left an undeniable mark on crime fiction as a whole and has remained an influence on the genre to the present day. Outside of his American origins, nowhere else has Stark’s series seemed more at home than in the pages of Il Giallo Mondadori — the iconic Italian series of translated pulps and crime novels. The very term ‘giallo’, now most recognizable for the film genre it spawned, comes from the brightly-colored covers of the Mondadori books. However, there is one Parker book that seems to have been at odds with the publishing company’s interests.

This blog has previously featured an article on The Sour Lemon Score and its significance as a piece of crime fiction and gay literature, and a recent look at the 1970 Italian edition has only served to prove that Stark’s stance was not only uncommon for the era but forward-thinking and perhaps downright radical enough to have translators find it necessary to actively cut, alter or destroy his original intent and content.

If you’re at all familiar with Donald Westlake’s bibliography, it’s evident that he’d had more than a passing fondness for the LGBT community. His dedication to accurately portraying his characters’ voices, the language being used has occasionally misled readers into taking his work to be on par with the general attitudes of the 1960s and ‘70s. That couldn’t be further from the truth.

The vast majority of Westlake’s books feature gay characters — A Jade in Aries (1970), written before the Stonewall uprising, revolves entirely around a supporting cast of gay men written with a sympathy and complexity rarely found elsewhere; the anthology Enough! (1978) makes mention of a married gay couple from San Francisco; Kinds of Love, Kinds of Death (1966), the first Mitch Tobin book, has the detective briefly delve into the eclectic home of a gay bodyguard; an even earlier example comes from the posthumously published Memory (written in 1963), which uses the term ‘gay’ as we understand it today in a surprising departure from the usual straight vernacular of the era; not to mention every other Parker (and Grofield!) book either references homosexuality or has at least one gay character with a speaking part.

That brings us to The Sour Lemon Score, often controversial in its sharp, layered, three-dimensional portrait of internalized homophobia. If Stark’s portrayal is visceral, it is never cruel. His characters are capable of horrific acts, but you understand the humanity behind them: denial, fear of being seen as ‘other’, a cutting commentary on the trappings of masculinity, etc. These are conversations the novel engages in because they matter to its author. On the other hand, the Italian translation uses language that not only was already outdated by the dawn of the 1970s but language that seeks to hurt, to disapprove, to paint as ‘wrong’.

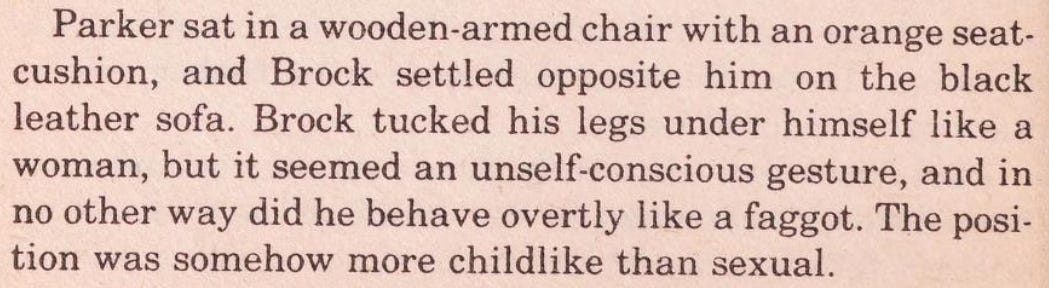

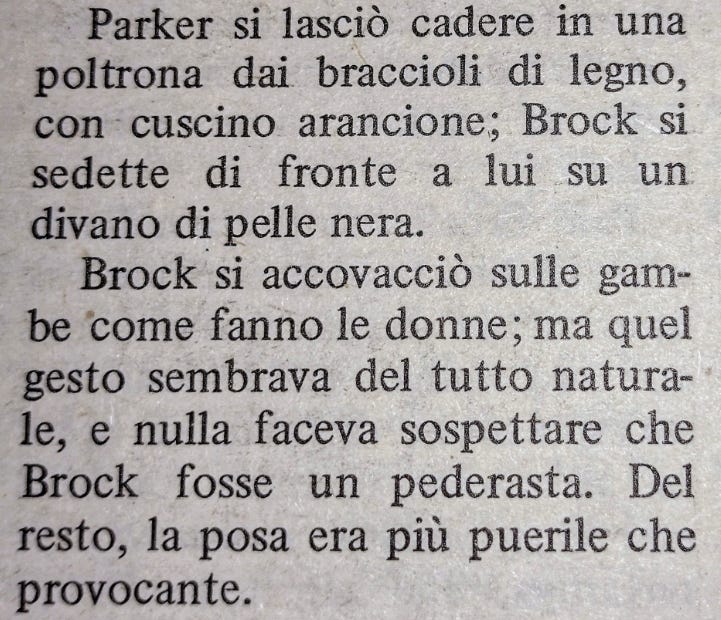

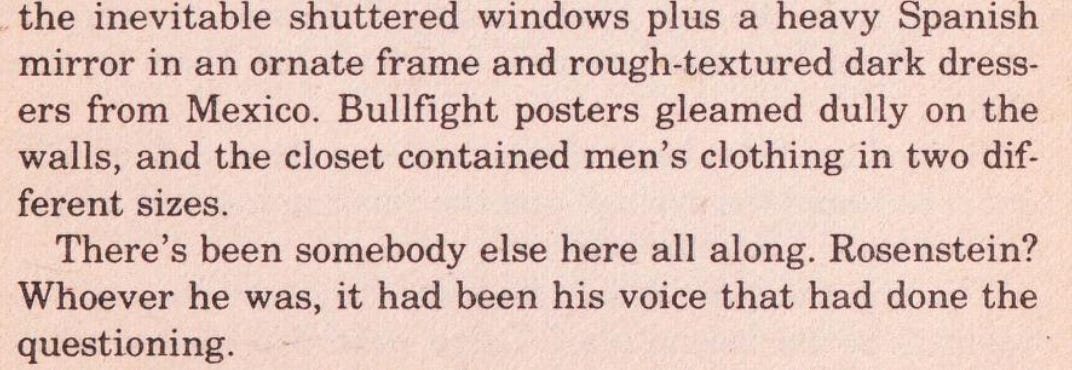

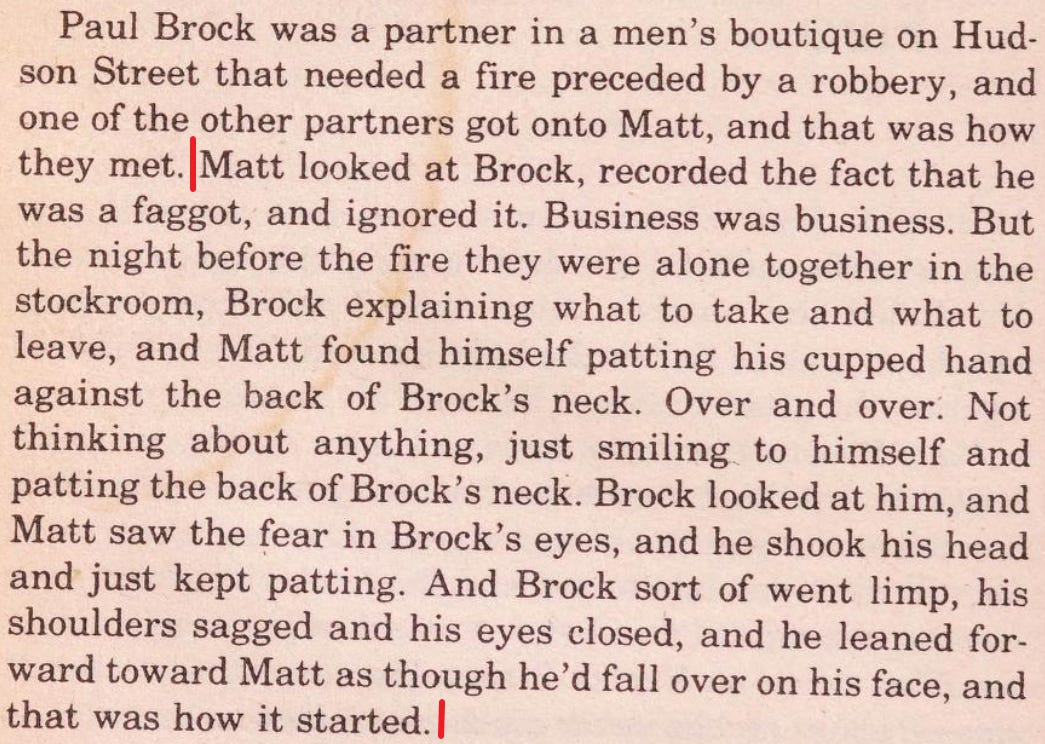

The use of the word “faggot” during Parker’s first meeting with Paul Brock has often been taken as a sign of blatant homophobia but there’s no real indication in the text that Parker objects to Brock’s sexuality, even without accounting for the gay subtext inherent to Parker himself as a character. When he discovers Brock lives with another man, he has no reaction whatsoever. In fact, no further word on the subject comes from Parker at all despite his continued interactions with Brock and his boyfriend, Matt Rosenstein, as a couple. To a man of his background and social class, a man who moves through the murky hyper-masculine heterosexual underworld, the slur in question is simply a descriptor for an effeminate man.

On the other hand, the Italian translation uses the term “pederasta” — pederast. Brock is “about thirty”, Rosenstein is forty-two; there is absolutely nothing in the novel — or indeed, any Stark novel — that could explain the word choice aside from the translator’s conflation of homosexuality with pedophilia. This isn’t Stark’s description of flamboyant mannerisms from Parker’s point-of-view, it’s a historically homophobic stance that’s almost shocking to encounter at all, let alone when it’s being used to alter the meaning of one of the most significant and fascinating gay-oriented books in the annals of crime fiction.

The majority of small moments between Rosenstein and Brock throughout the novel remain the same, their relationship hasn’t been entirely erased but the tone is set by that initial change.

Rosenstein says “mio caro” — “my dear” — instead of “baby”, but the meaning stays the same.

Parker’s “angel” is translated as “treasure”.

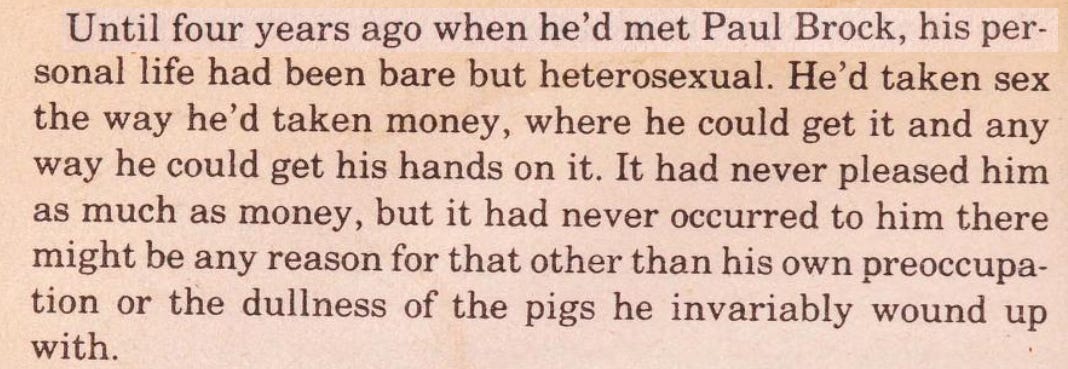

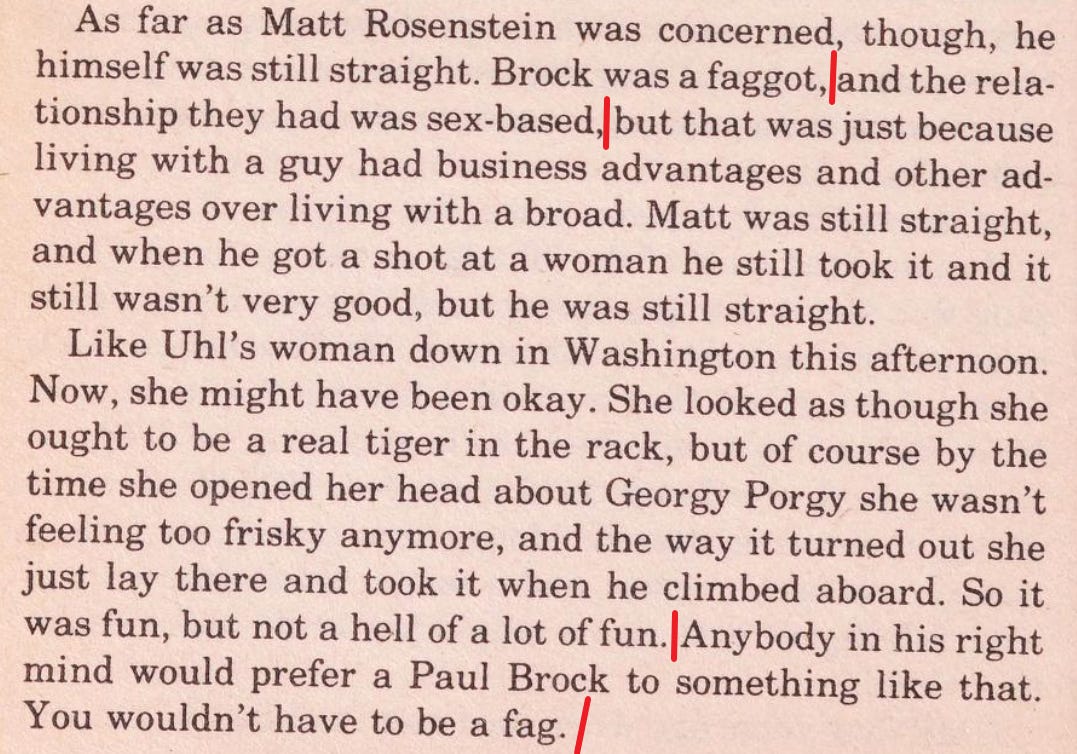

It’s during Rosenstein’s POV chapter, that hard-hitting and heartbreaking exploration of internalized homophobia, that the most major alteration comes. In this particular instance, Stark’s work isn’t just tonally different — it’s outright censored. The red lines in the images below mark the excerpts missing from the Italian version:

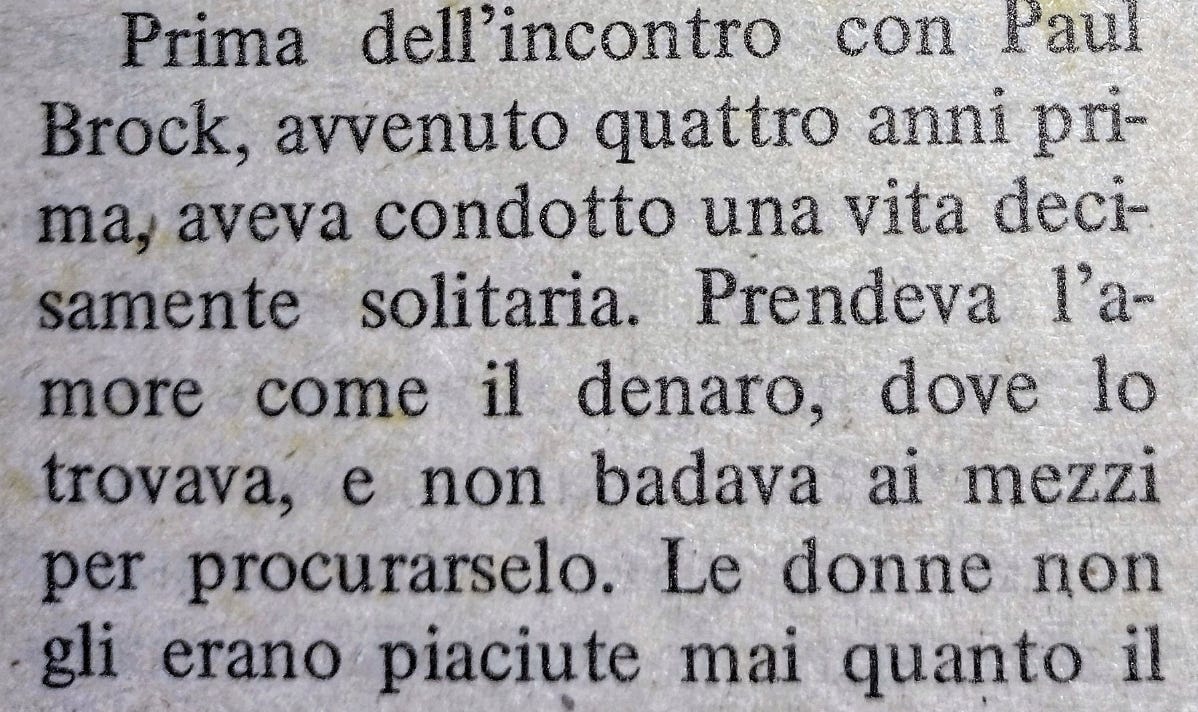

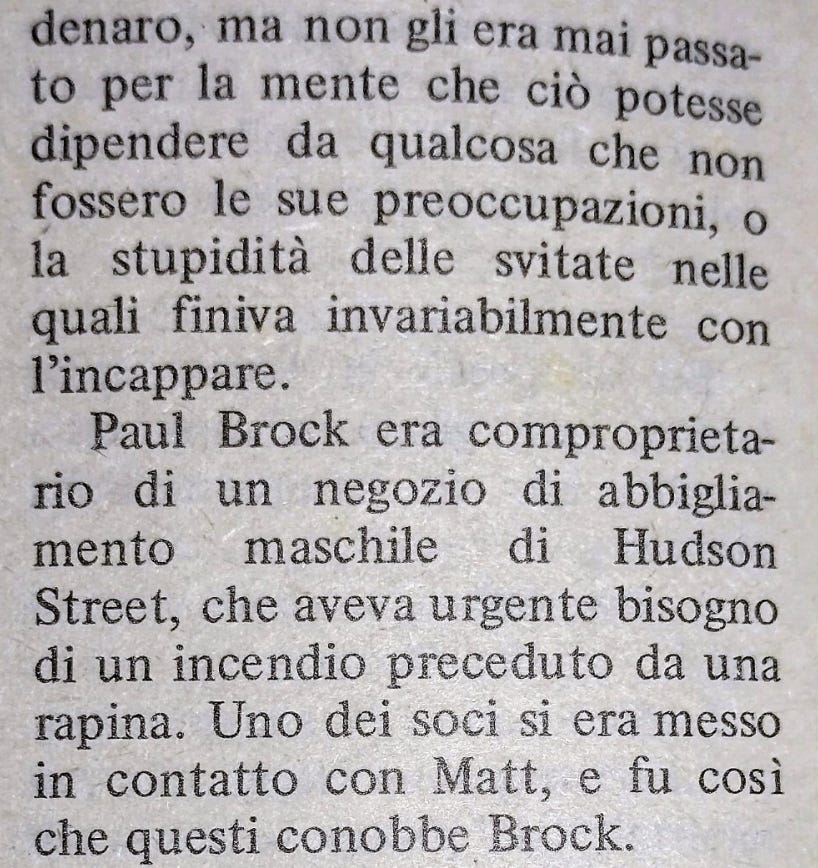

The Italian translation doesn’t say Rosenstein’s personal life had been “bare but heterosexual” until he’d come to realize his sexuality, instead “aveva condotto una vita decisamente solitaria” — “he’d led a decidedly solitary life”. The next paragraph, detailing his meeting with Brock and the beginning of their romantic relationship, ends at “and that was how they met”. There’s no grand discovery, no rare affection from a man who’d never known himself until that moment, Rosenstein and Brock are denied their first kiss. A great big chunk, a pivotal part of Sour Lemon’s tale, is resolutely amputated.

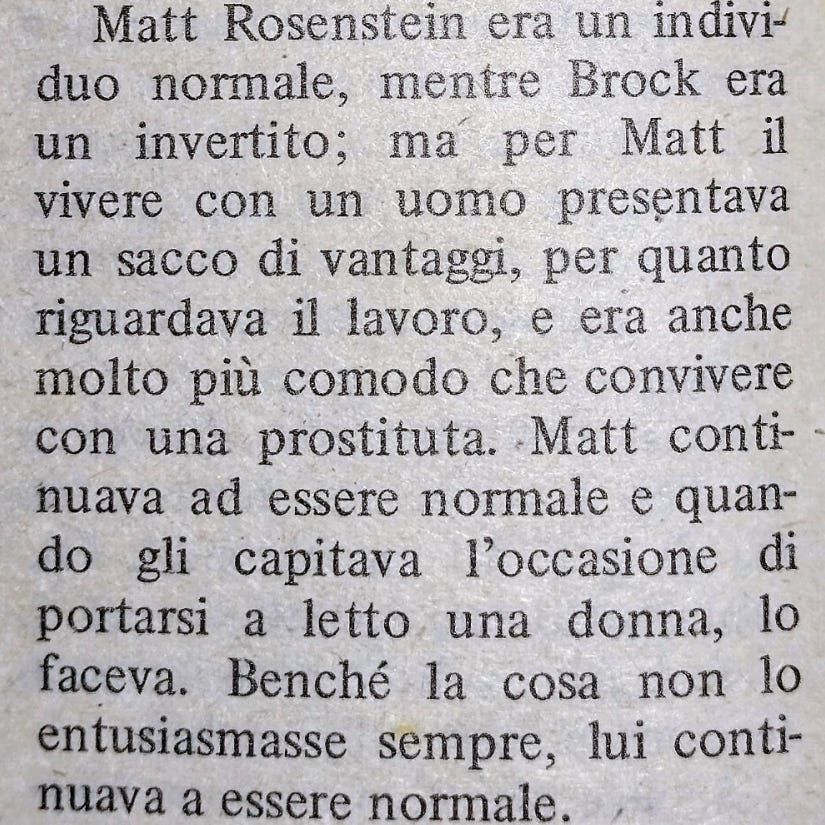

The following paragraph doesn’t call Rosenstein “straight” and Brock a “faggot”, an unkind but decidedly characteristic term from a man struggling with his own sexuality, but rather “normal” and an “invert”. The sentence regarding their relationship being sex-based is cut out completely, despite the fact that a novel belonging to a genre primarily read by straight male audiences making an explicit reference to gay sex remains positively unheard of now and certainly revolutionary at the time.

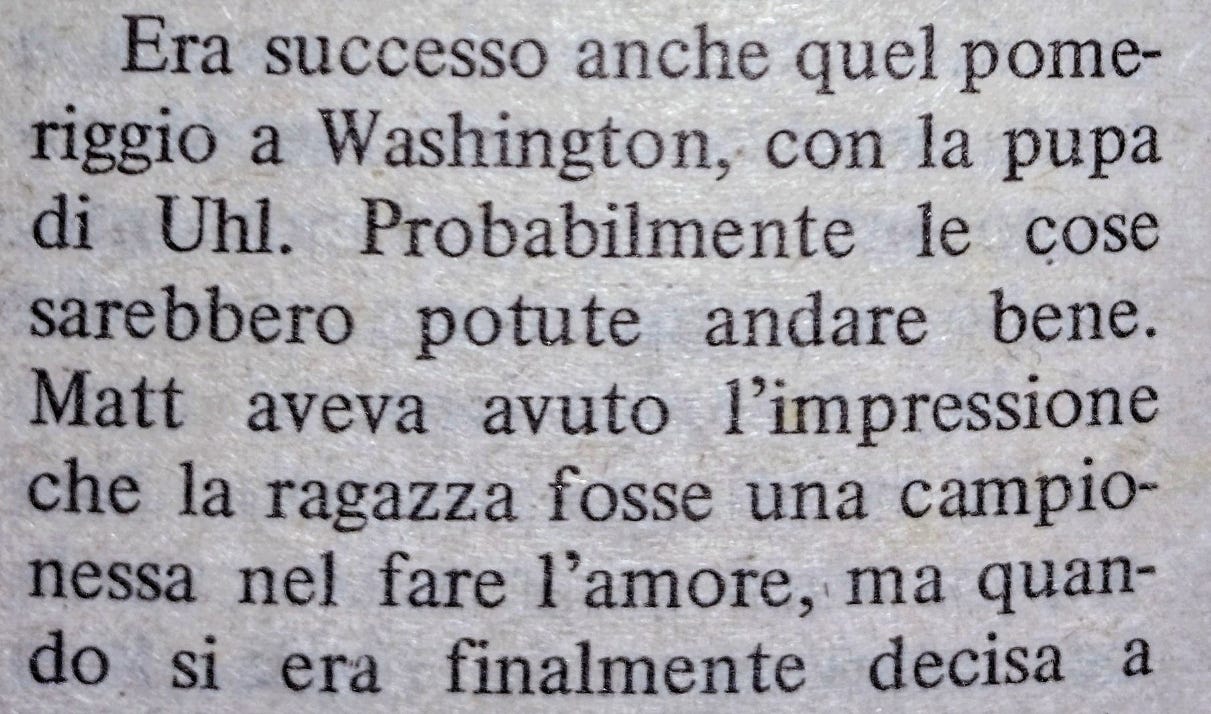

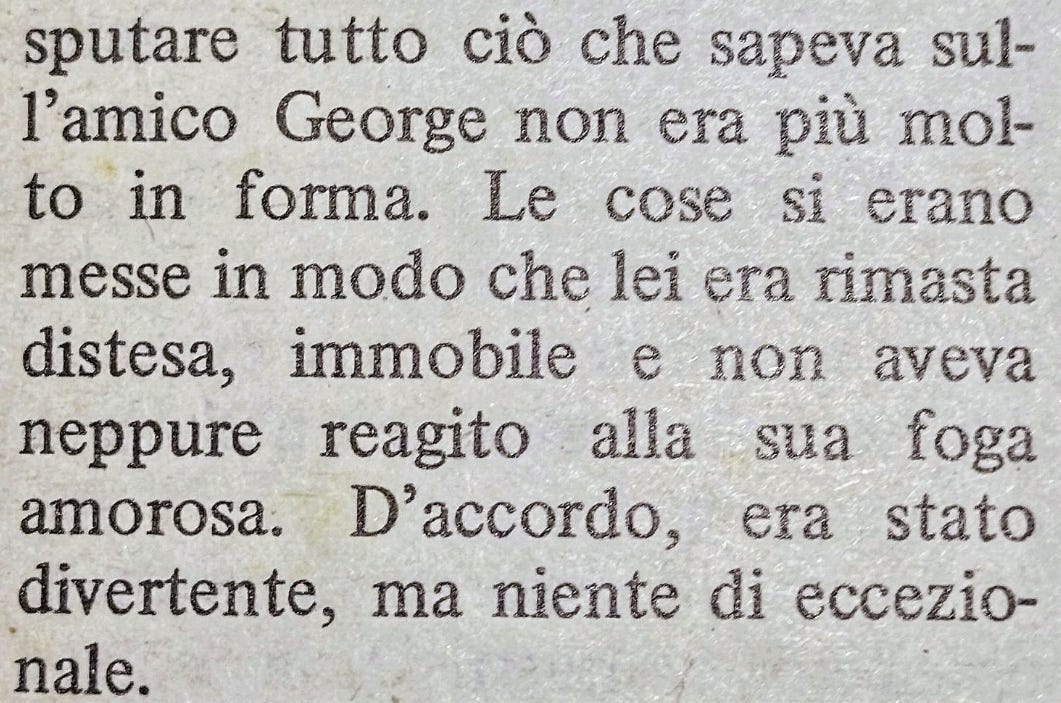

The final part ends with Rosenstein’s latest attempt at a heterosexual dalliance, the Italian version phrases it as “it was thrilling, but nothing exceptional” and makes no mention of the fact that Rosenstein prefers Brock’s company — prefers a man, sexually and romantically.

In effect, The Sour Lemon Score is rendered toothless by Mondadori. There is no sign that these books are abridged, there is no apparent difference in any other chapters or sections but the novel was still altered and censored in the interest of homophobia. If nothing else, there is no clearer evidence that where Donald Westlake stood in the 1960s was decades and decades ahead of general attitudes towards the LGBT community.