tough business:

a parker site

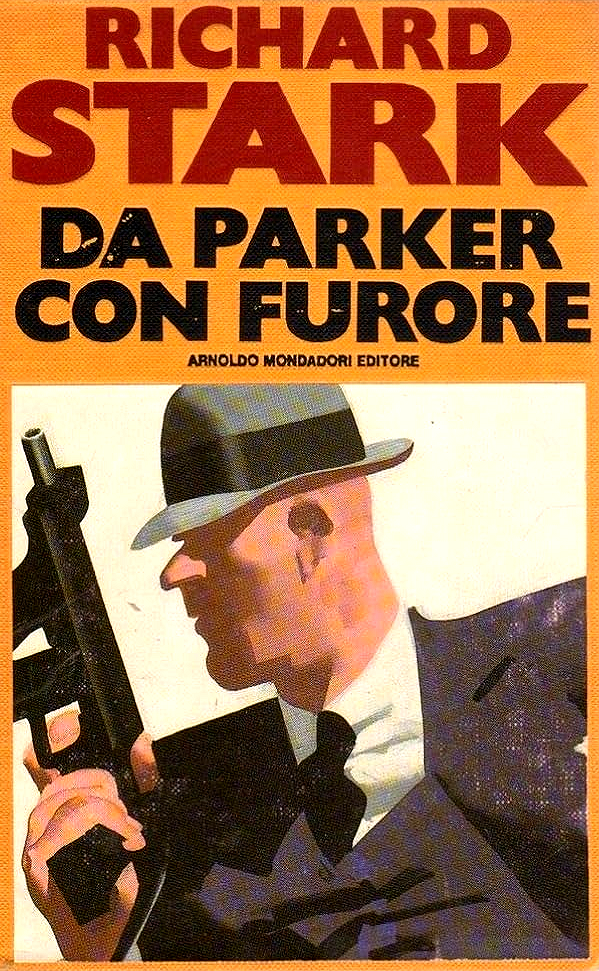

Da Parker Con Furore | From Parker With Fury - Foreword

The October 1987 Da Parker Con Furore (From Parker With Fury) omnibus released by Mondadori includes an especially insightful foreword by Italian journalist and translator Laura Grimaldi. It stands out as a rarity of particular interest for its analysis of the Parker series on a historical basis from a non-American point of view, and its acknowledgement of Alan Grofield as a co-protagonist of the series and a complementary character to Parker.

See our English translation below, as well as the original Italian text.

A Man Called Parker

Parker (no first name) is certainly more famous than his author (Richard Stark, pseudonym of Donald Westlake). People remember him immediately, without hesitation. Parker? Yes, of course, the tough one, the "noir". The same phenomenon as Fantômas, Arsène Lupin, Sherlock Holmes. When people remembering him, say "noir", they're not only referring to the fact that in Italy an imprint was created especially for him, called Neri Mondadori, because he, Parker, was too unorthodox, too violent, too "out of line" to appear in the more classic series of crime novels without disorienting readers. They're also referring to the concept of French Noir, the concept of "maudit", which was valid for Jim Thomson [sic], James Hadley Chase, Cornell Woolrich and a few others.

Parker, to his author, is an ordinary man. Donald Westlake, in fact, has a sort of reverence for professionals (the others, the amateurs, don't interest him. Humanity, to him, should only be made up of professionals) and among these, he includes doctors, lawyers, businessmen, criminals -- all under the same umbrella, none with particular human qualities or moral impulses. A job must be done, and done well; whether it is a balance sheet, a speech, a robbery, or a diagnosis. And Parker does his jobs very well, so much so that in the end he'll have his score and revenge because the impulse that moves him, in addition to having chosen theft as a method of supporting himself, is a distant resentment towards some of his accomplices who -- believing him to be dead -- had abandoned him*.

What makes him interesting is his methodology: through trial and error, he has developed an almost perfect way of working, and if the unforeseen leaves room for some mistakes, it is rare that Parker causes them. If anything, it's an accomplice that doesn't respect his orders, or a boy who's lingered too long at night with his girlfriend and crosses the street while a major robbery is taking place*.

The same goes for violence. When it's instrumental to the success of a hit, there must be no hesitation. The obstacle must be removed, quickly and promptly. With a hand on a throat, with a burst of machine gun fire, with a revolver shot. The means aren't important, only the end counts. But if the situation absolutely doesn't require violent intervention, then Parker has a theory that he regularly puts into practice. Hostages, for example, should not be frightened or intimidated. "What's your name?" "Donald." "What do your friends call you? Don? Well, Don, be good and stand quietly in that corner," said in a calm, almost paternal voice.

A man like that can carry out extremely complex plans, can select the right men and assign them the right role, can even emerge at the end of the novel with the money in his pocket. But that doesn't mean Richard Stark makes him a hero (just as Donald Westlake will not make Dortmunder a hero later on). "Heroes don't exist," claims Stark-Westlake. "They are the invention of inferior literature, of filmmaking, of political power, of criminality." Men exist, simply put. And policemen? Those who should be Parker's natural enemies? They, too, almost cease to exist. They are immobilized, rendered harmless, worn out, unfeeling. For Stark (and again, for Westlake as well), the police are either corrupt or inept.

He has chosen "the others", the "different", as the protagonists of his novels; but the message he conveys is clear: what is the difference between the president of a multinational corporation whose way of making money is selling weapons, and someone like Parker, whose way of making money involves leaving a couple people on the sidewalk? And what is the difference between a cop who always has his .38 in hand, ready to use it, and a criminal who gets his weapons on the black market? According to the rules of Law and Order, the policeman is always right because he defends the community from the violence of others. But Stark-Westlake doesn't believe it. In New York, the police have often been accused of corruption, and when it's gone nowhere it's only because some powerful politician managed to protect them. An anarchist, then? A nihilist? Neither. Just a citizen looking at society with his eyes wide open.

Richard Stark's protagonists are obsessed with taxes, just like all other Americans. "You can get away with any crime. With murder, with robbery, with kidnapping, but not with tax evasion." While they are preparing for a job, or about to carry one out, the robbers wonder what's the best way to declare their "income"*.

For doctors, Stark has the same lack of respect that Westlake will reveal in the novels written under his own name. In the Parker books, doctors subsidize heists under the table at one hundred percent interest. In the Dortmunder books, they always own luxury cars (which they can afford out of pocket money that's not exactly legitimate), and are the target of Andy Kelp, Dortmunder's right-hand man, who when he has to steal a car for a job -- or to get around the city -- always chooses those with M.D. plates.

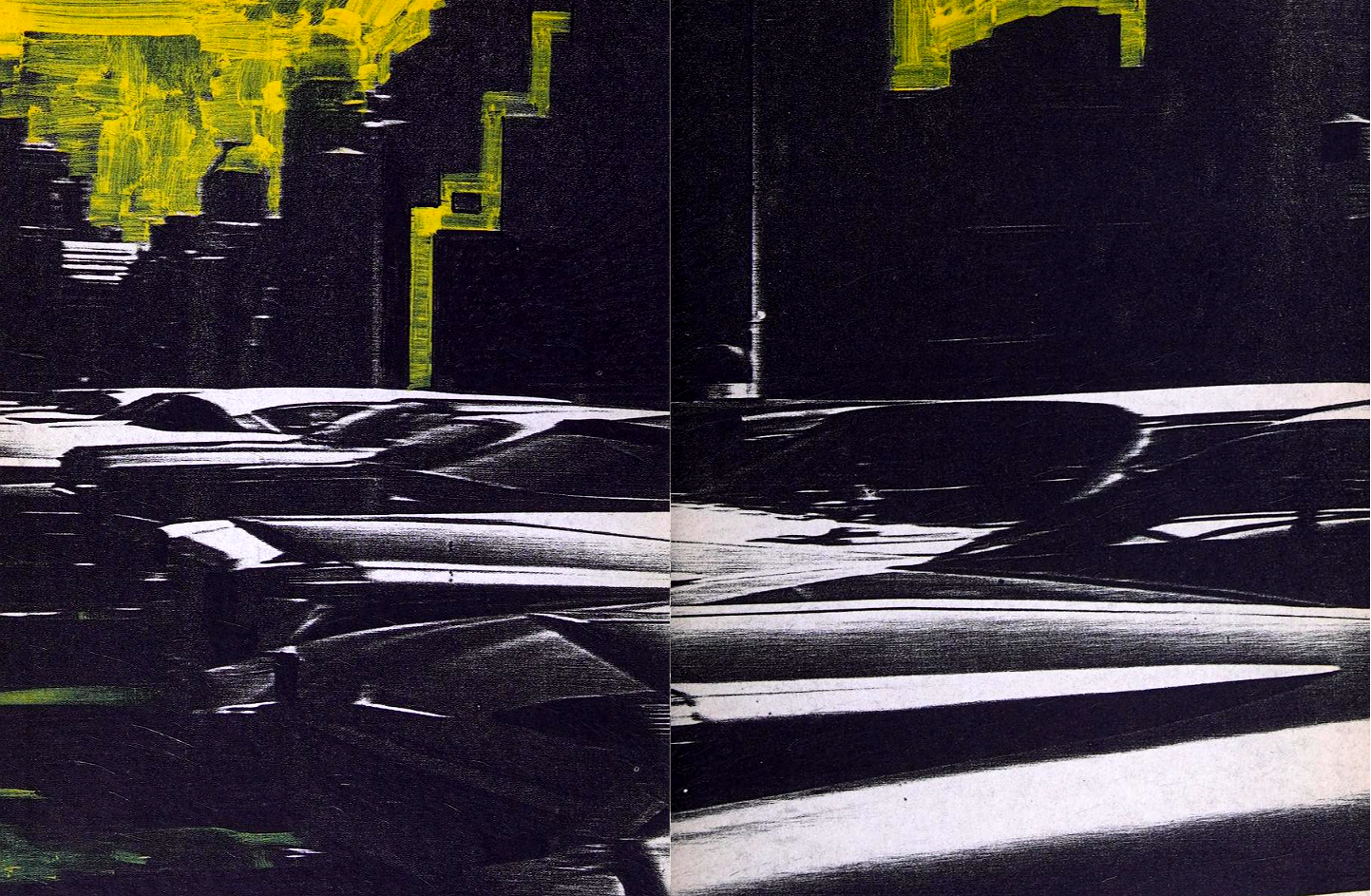

Inside cover of the omnibus. Art by Ferenc Pinter.

The unforgiving (or realistic?) outlook Donald Westlake scrutinizes the world with started in 1960 with the publication of his first novel, The Mercenaries. Since then, he's never stopped telling stories "from the inside" of criminal organizations, with the exception of the short-lived series starring the ex-cop Mitch Tobin signed by Tucker Coe.

But it was in 1962 that Westlake, under the pseudonym of Richard Stark, first imposed himself on American critics. The Hunter, released in Italy under the title of Anonima Carogne [Anonymous Carrion], marked Parker's debut. And it marked the beginning of the author's uninterrupted success. Lee Marvin fell in love with the role of the "full-time thief" and, under John Boorman's direction, created a memorable Parker in a film that will go down in cinematic history: Point Blank [Italian: Senza un attimo di tregua.]

These are the years of a restless America, an American that questions itself. And to question itself and make others question it, Westlake uses the medium of the thriller. In an era in which emotions are ideological, he decides to completely strip the plot of any emotion. He has a sort of brevity in using adjectives, and when he does use them, he chooses the leanest ones. It is the facts and the actions that must speak, not the words. And when that is not enough, he resorts to irony and creates Dortmunder, who is nothing more than a grotesque version of Parker.

In a world where consistency is on sale for cheap, Westlake remains true to himself. A very prolific author, he's written about sixty novels and some collections of short stories, but his inspiration remains fresh and his inventiveness intact. When he realized that the character of Alan Grofield -- who has a supporting role in the Parker novels -- is perhaps more captivating as a protagonist, he began a series specifically for him, and as if that were not enough, he ended up creating two parallel novels; one with Parker and one with Grofield, in which he described the same adventure seen through Grofield's eyes in The Blackbirds [sic] in 1969, and through Parker's in Slayground in 1971.

As much as Parker is solitary, hardened, cynical, Grofield is creative in the broadest sense of the term. Grofield is an actor, he feels like an actor, and to finance that activity he commits robberies. The theater is his life, and when he can't act and he's holding a machine gun in his hand, he hears a kind of soundtrack in his head; a rhythmic music, always different, accompanying his criminal activities. Or does it isolate him from his criminal activities, locking him in his own private show? The fact is that Grofield and Parker, just like Kelp and Dortmunder, are two practically complementary characters. Parker must have someone to trust, someone -- when necessary -- to chew out. Just as Dortmunder needs someone on whom he can unload his frustrations, his moments of sadness, his depression. Grofield and Kelp are the "sidekicks" of the two protagonists, but they are also essential to the stories. And Richard Stark realizes this to the point that when he decides to end the Parker and Grofield series, to deal only with the "infallible five" of the Dortmunder novels, he does it in a splendid swan song; creating a novel in formidable shades, perhaps the most violent he's ever written, certainly the longest and most complex. The title is Butcher's Moon and the year is 1974. Co-protagonists, ex aequo, Parker and Dortmunder.

Selecting four novels that exemplify Stark's output is both difficult and simple. Difficult because the character of Parker, always "in progress", seems to have something new to tell us in each adventure and it seems like only the full series could provide a truly complete portrait of him. Simple because the novels are all unparalleled and highly tense. The last great robbery committed by the two friends-partners*, Butcher's Moon, could not be left out. For the other three, the criteria was the temporal scansion (The Score is from 1965, The Green Eagle Score from 1967, and Deadly Edge from 1974*) and the extraordinary nature of the heists. Four robberies done by the book, with a cast of characters who stand out to this day for their clarity and impact.

Original text:

References:

- Referring to the events of The Hunter.

- Referring to the events of The Score.

- Referring to the events of The Score.

- The rhyme in the phrase "amici-complici" can't be fully translated into English, but the tone in reference to the Parker-Grofield dynamic is worth noting.

- A small error, Deadly Edge was published in 1971.