tough business:

a parker site

Seismic Shifts: Donald Westlake and the Language of Change

It's not uncommon for a writer to return to a certain theme, to reuse a certain phrase, to depend on certain language to describe a specific phenomenon – it's not uncommon, but it is rarely meaningless. The great recurring theme of Donald Westlake's work is that of identity, and nowhere else is that more apparent than in the flurry of work he'd done throughout the 1960s, his prime and the most productive period of his career.

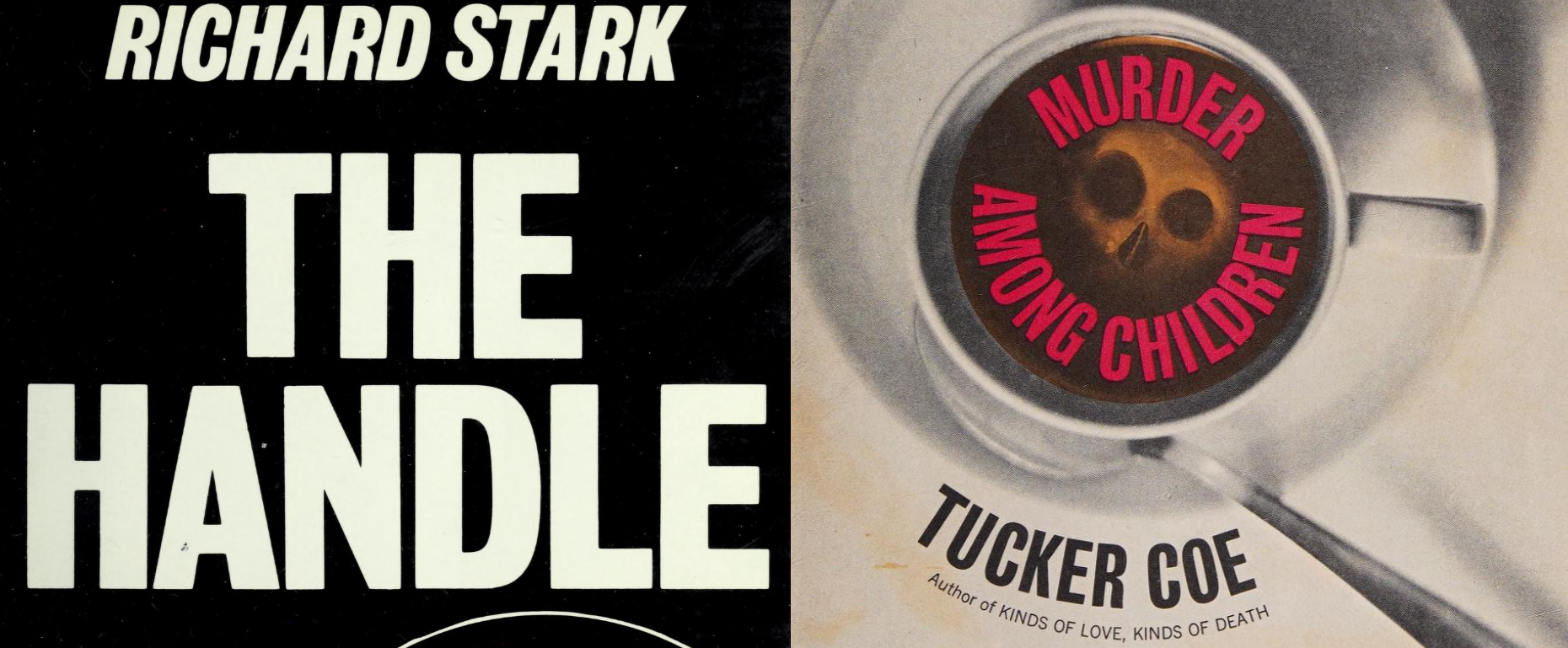

Between 1960 and 1969, he wrote forty-seven novels; sometimes up to eight a year. It was also during this time that his best known alter-egos emerged. Richard Stark wrote cold, blunt, hard-boiled crime fiction; Tucker Coe wrote overtly emotional mystery novels about an open-wound of an ex-cop. At first glance, these two major highlights of Westlake's '60s output couldn't be more different – and yet, in many ways, they are mirror images of each other. Although widely debated in the case of Richard Stark’s infamous cold-blooded protagonist, the stories told by Coe and Stark are still those of men gradually opening up to the world around them, and being transformed through their relationships with other men.

The Tucker Coe books all revolve around P.I. Mitch Tobin interacting with various groups of outsiders (criminals, bohemians, mental patients, the LGBT community, etc.), and finding his place among them after some life-changing trauma had flung him away from the straight and narrow. Tobin regains his humanity not by returning to the world of law and police and precinct politics, but by turning his back on it and accepting his own status as outsider.

On the other hand, Richard Stark’s Parker starts out as an outsider and remains the same – in fact, it’s hard to imagine him as anything else. The slow change that takes place is much more subtle than with Tobin, and plays mostly in subtext; hence necessitating the entirety of the original sixteen books to Tobin’s five. Still, the Parker we meet in The Hunter (1962) is not the Parker of Butcher’s Moon (1974). Like Tobin, Parker grows through the friendships he makes along the way. He never does soften, but he certainly develops as a character, and his dynamic with flamboyant actor Alan Grofield reveals a degree of loyalty and kindness that shocks in and out of universe. Like crime novelist Dennis Lehane recently stated, “if he feels anything at all, it's for Grofield.”

Published within a year of each other, The Handle (1966) and Murder Among Children (1967) both mark the catalyst for the thaw taking place within Parker and Tobin, and it is a sentiment that is expressed and explored in startlingly similar ways.

The ending of The Handle picks up after Parker had saved Grofield’s life – for the first time, but certainly not the last. The warmth of Grofield’s gratitude is a foreign thing to Parker; he dismisses it as, “we were working together,” but it is clearly the beginning of something much more complex than any professional relationship Parker had previously had. The Handle doesn’t just lay the groundwork for Grofield’s later appearances in his spin-off series, but for Butcher’s Moon as well; in which Handy memorably declares that Parker wouldn’t do this for anybody else (“That’s not like you. [...] For one, to go to all this trouble for somebody else. Grofield, me, anybody.”) In effect, this marks the start of a pattern, and accounts for the intensity of Parker’s subsequent feelings about Grofield being in danger. The scene strikes as being one of monumental importance, primarily in ways that only make themselves known in the series’ final installment.

Murder Among Children, ending on a similar note of friendship, has one of the ‘bohemians’ Tobin meets over the course of the mystery express his pleasure at having worked with him. Hulmer Fass, a black young man running in the same circles as Tobin’s niece, becomes something of a sidekick and partner to Tobin – their friendship eschews generational gaps, racial dynamics, social class differences, and allows Tobin to start opening up about the trauma he’d suffered. This warmth he feels, the sudden proximity to a humanity he’d thought lost to him, is as unfamiliar to him as Grofield’s gratitude is to Parker.

The language being used here is near-identical (the knowing “that’s right”, the easy casual “so long” rife with genuine sentiment, blunt conversation carefully concealing underlying affection), as is the setting within the context of two novels published so close together (Tobin’s release from jail and his relief at seeing Hulmer mirroring Grofield’s rescue, both events serving as an understated turning point in Stark and Coe’s respective protagonists’ lives). But whereas the change Tobin is undergoing is clear-cut and obvious under the banner of friendship, Parker’s side of things is – intentionally – murky. Hulmer and Tobin have no previous relationship, an ending establishing their shift from associates to friends is only natural. But what is changing about Parker and Grofield’s dynamic in The Handle?

Richard Stark’s co-protagonists had already been friends prior to Grofield’s first appearance in The Score; and even back then, Parker thinks of Grofield as a good man to work with, going as far as to describe him as “intense and handsome”. There is another dimension to their dynamic here, a heavily layered one. If the language used denotes change, as it undoubtedly does in Murder Among Children, then one can’t help but notice it also gives way to subtext: the sly sensuality of Grofield’s words, his pose on the bed, Parker’s unprecedented concern. The reader need only wonder how The Handle’s ending would read had it been a woman in bed in that Mexico City hotel room.